We Were Great Tenants. The Algorithm Didn’t Care.

by Kent O. Bhupathi

Earlier this year, my wife and I made what should’ve been a simple request: a short-term lease extension while we explored buying a home. We loved our townhouse. Paid rent on time. We weren’t just tenants; we were good ones. Reliable, respectful, well-liked by the front office.

So when we asked about continuing our lease month to month, or even for just a few extra months, we expected at least a conversation.

What we got was a price sheet.

The cost to stay? A 90% increase. No negotiation. No consideration of our payment history or community ties. Just a single line: “This is what the system says.”

We later found out that “the system” wasn’t just a euphemism for company policy. It was a literal pricing algorithm, an increasingly common, powerful force in the U.S. housing market that determines rent levels with zero human judgment, and even less empathy.

That single moment, when we were told we could pay twice as much for reduced housing security, triggered a months-long period of research and reflection. Why is renting becoming so unaffordable and unaccountable? What do renters truly need to know?

Turns out, what seems like irrational pricing is actually part of a deeply rational, if disturbing, system. One that’s engineered for growth, not fairness. And one that’s making it harder than ever for everyday families to afford a place to live, let alone save to buy one.

The Myth of the “Counterbalance”

There’s a familiar assumption that floats through media and money advice circles: when home prices rise, rent levels off; when rents soar, homes become more affordable. The idea is that renting and buying are counterbalancing forces.

But that’s not what the data says.

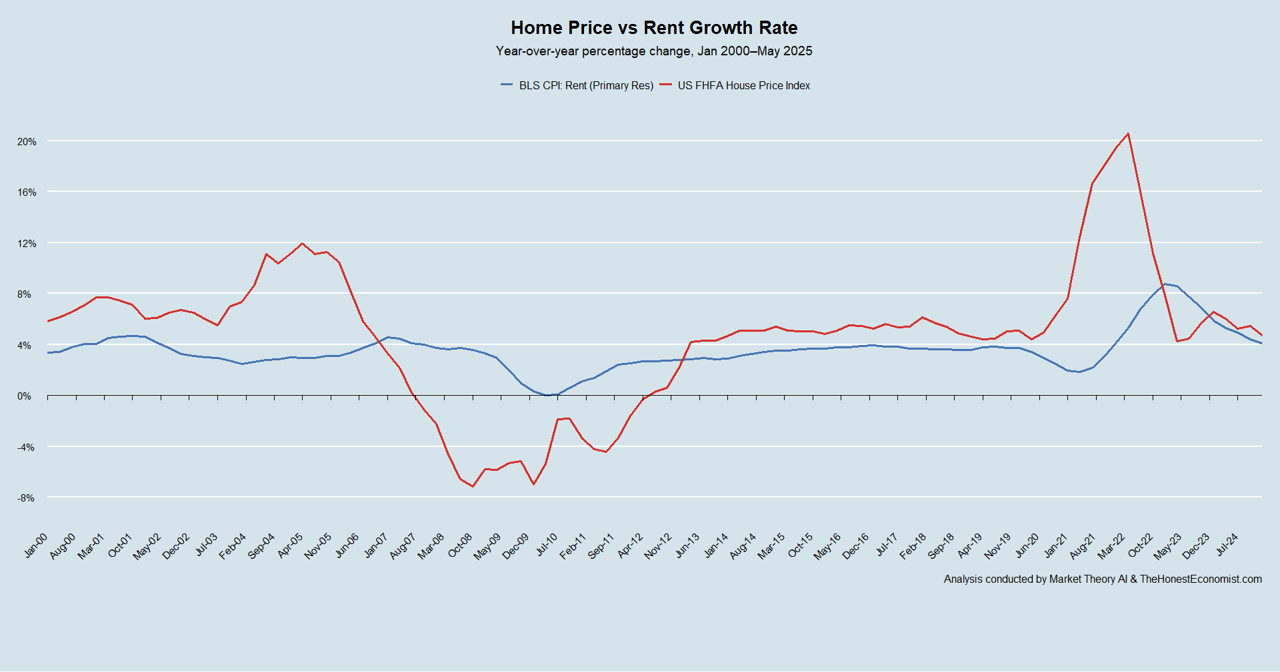

According to the latest Consumer Price Index report, core inflation increased by approximately 2.4% over the past year, yet rents rose by nearly 4% during the same period. The Federal Housing Finance Agency similarly notes an increase in home prices exceeding 4.5%. In contrast, energy prices fell by almost 9%, food prices grew by less than 3%, and the price of a new car saw only a marginal rise of about half a percent. Among these categories, it is clear that shelter stands out as the primary driver shaping our current inflationary landscape.

Historically, however, this isn’t new. Rents almost never go down, even in recessions. From 2008 to 2010, as home prices plummeted, average U.S. rents barely moved. During the brief COVID downturn, national rents decelerated, but remained positive year over year.

Economists call this “rent stickiness.” Landlords tend to avoid lowering nominal rent. Instead, they might offer temporary concessions, like a free month or waived fees, but rarely cut the base rate. The Bureau of Labor Statistics' rental components confirm this year after year.

Meanwhile, home prices behave more like a volatile asset. They spike. They correct. They crash. For buyers with timing, savings, or luck, there’s at least a chance to win. Renters? Not so much.

Why Rent Is a One-Way Street

Unlike groceries or gas, where consumers can substitute or reduce consumption, housing demand is mostly inelastic. People need shelter. They can’t cut back on square footage the way they might on dining out. And this allows rents to keep inching, or lurching, upward.

Rent growth is also tied to broader inflationary forces: property taxes, insurance, maintenance costs, and rising wages. But more importantly, rents are structured to climb. Leases typically last a year, and many build in automatic annual increases. Once set, those increases are rarely reversed.

Compounding this, housing supply has lagged behind household formation for more than a decade. A Brookings analysis reports show that post-2008 underbuilding, restrictive zoning, and lengthy permitting delays have left the U.S. with millions fewer units than needed. In markets with tight vacancy rates, this gives landlords pricing power with few constraints.

Still, these conventional explanations don’t account for the peculiar, erratic patterns we saw firsthand while apartment hunting. Why would a six-month lease cost $4,200, but a seven-month lease jump to $7,250? Why would the rent for our old unit, still vacant months later, be priced so high that the building earned nothing rather than make a reasonable deal?

That’s when we stumbled on something darker: rent is no longer just a market signal. It’s a managed number.

Enter the Algorithm

Over the past decade, algorithmic pricing has quietly transformed how rents are set. Real estate tech firms like RealPage have developed systems that ingest vast amounts of market data, including actual lease transactions from competitors, and use AI models to calculate optimal pricing. These models run daily. They remove negotiation from the equation and adjust rents with mathematical precision.

This approach, pioneered in the airline and hotel industries, is now deeply embedded in real estate. RealPage software alone has been used to set prices for nearly 20 million rental units, with adoption rates exceeding 70% in some city submarkets.

The software doesn’t just set rent. It sets the tone. Leasing agents are told not to deviate from algorithmically recommended prices. Human input is minimized. Uniformity is maximized. And this removes the one thing that might have helped someone like me: a conversation.

What’s more troubling, research and industry testimony show these algorithms often recommend leaving units vacant to preserve pricing power. Executives have admitted that operating at 94% occupancy with higher rents can be more profitable than filling every unit.

A Market That’s Forgotten How to Compete

In theory, markets are supposed to self-correct. If rents rise too high, landlords lower prices to fill units. But when multiple landlords use the same software, all benchmarking against each other, the incentive to undercut vanishes. Everyone holds out. And the software, fed by the same data, recommends the same high price.

This isn’t explicit collusion. But it’s not competition either. It’s tacit algorithmic collusion: a digital form of price-fixing that’s hard to prove, yet profoundly effective. So effective, in fact, that the Department of Justice and several state attorneys general have launched investigations into its anticompetitive effects.

In the meantime, families like ours pay the price. Or walk away.

What You Can Do: Fighting Back, Strategically

We don’t have to accept that the algorithm always wins. Here are several ways renters and citizens can and should push back:

Fight algorithms with algorithms. Use rent-tracking tools, open-source pricing monitors, or services that flag overpriced units and declining occupancy. One example with which I am familiar is Rentometer.com (not sponsored), a platform that offers rent comparison data to help assess local pricing.

Document and report algorithmic pricing experiences. Share uniform pricing, refusal to negotiate, or erratic term-based pricing with your state Attorney General or the DOJ.

Use algorithm logic against itself. Offer to sign longer leases or pre-pay rent (where available). Algorithms often reward occupancy certainty.

Target lease-up periods and oversupply. New developments may offer better deals as they race to meet investor benchmarks.

Support rent-stabilization policy. Back vacancy taxes, inflation-linked rent caps, and municipal rent indices that limit runaway increases. Call your local representatives!

Year-on-year growth in US home prices (red) has proved much more volatile than rent inflation (blue) over 2000-2025. Home values surged during the mid-2000s boom, fell steeply in the Great Recession, recovered through the 2010s, and spiked above 20% during the pandemic before decelerating sharply. Rent growth, by contrast, has largely stayed within a 2–5% corridor, dipping only briefly in downturns. The latest readings for 2024-25 reveal home-price appreciation cooling while rent inflation moves back toward its long-run range, highlighting that shelter costs rise persistently yet the purchase market remains far more cyclical, creating distinct risk and timing considerations for renters and prospective buyers.

Conclusion: We Deserve Better Than “Take It or Leave It”

As our old townhouse continues to sit empty (now over three months), I couldn’t help but think: they could’ve had a reasonable tenant. A known quantity. But instead, the algorithm chose nothing over a fair deal. And, ironically, this still made financial sense to the management company.

That’s the problem.

We live in a housing market where human need is weighed not against fairness or community, but against abstract formulas. And those formulas are designed, above all, to grow yield.

If homeownership still offers moments to capture upside, to buy low or refinance wisely, renting offers none of those levers. It’s a treadmill on a slow incline. No equity, no stability, no recourse.

That is, of course, unless we change the system.

It starts with understanding the dynamics at play. And it continues with collective action, smart, strategic, evidence-based efforts to make the housing market a little more human again.

Because “what the system says” shouldn’t be the last word.

Sources:

Bauer, Lauren, Eloise Burtis, Wendy Edelberg, Sofoklis Goulas, Noadia Steinmetz-Silber, and Sarah Yu Wang. "Ten Economic Facts about Rental Housing." Brookings Institution, March 21, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/ten-economic-facts-about-rental-housing/.

Bruen, Chris. Recession Risks and Inflationary Pressures: Impact of Economic Uncertainty on the Apartment Industry. Research Notes. Washington, DC: National Multifamily Housing Council, March 2025. https://www.nmhc.org/contentassets/1bbf076b44234c29b5f94ce77b47efe7/2025-march-research-notes.pdf.

Coven, Joshua. The Impact of Institutional Investors on Homeownership and Neighborhood Access. May 13, 2025. https://joshuacoven.github.io/assets/JoshuaCovenJMP.pdf.

Davis, J. Scott. "Evidence Suggests U.S. House Price/Rent Ratio, Real Home Prices to Decline." Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Economics Blog, February 25, 2025. https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2025/0225.

Diamond, Rebecca. "What Does Economic Evidence Tell Us about the Effects of Rent Control?" Brookings Institution, October 18, 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-does-economic-evidence-tell-us-about-the-effects-of-rent-control/.

Edelberg, Wendy. "What Can the Next Administration Do about the US Housing Shortage?" Brookings Institution, October 24, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-can-the-next-administration-do-about-the-us-housing-shortage/.

Ellen, Ingrid Gould, and Laurie Goodman. Single-Family Rentals: Trends and Policy Recommendations. Washington, DC: The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, November 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/20231102_THP_SingleFamilyRentals_Proposal.pdf.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "Is the Housing Price-Rent Ratio a Leading Indicator?" FRED Blog, September 10, 2018. https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2018/09/is-the-housing-price-rent-ratio-a-leading-indicator/.

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. America’s Rental Housing: Meeting Challenges, Building on Opportunities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2011. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/ahr2011-2-rentalmarketconditions.pdf.

Loewenstein, Lara, and Paul S. Willen. House Prices and Rents in the 21st Century. NBER Working Paper No. 31013. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2023. https://www.nber.org/papers/w31013.

National Association of Home Builders. "Harvard Report Shows Stakeholders Must Address Housing Affordability Crisis Together." NAHB Now, June 21, 2024. https://www.nahb.org/blog/2024/06/stakeholders-must-address-housing-affordability-crisis-together.

The Real Estate Roundtable and Nareit. Comment Letter on the Federal Trade Commission’s SFR Housing Study, P251200. Submitted to the Federal Trade Commission, March 24, 2025. https://www.rer.org/wp-content/uploads/RER-Nareit-FTC-Comment-Letter-on-SFR.pdf.

RealTrends Verified. "U.S. Senators Ask the DOJ to Investigate RealPage." RealTrends, March 6, 2023. https://www.realtrends.com/blog/2023/03/06/u-s-senators-ask-the-doj-to-investigate-realpage/.

Schuetz, Jenny. "Where Have All the Houses Gone: Private Equity, Single-Family Rentals, and America’s Neighborhoods." Brookings Institution, July 1, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/where-have-all-the-houses-gone-private-equity-single-family-rentals-and-americas-neighborhoods/.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. "What Can the Great Recession Teach Us about Rent Affordability in the Age of Coronavirus?" WatchBlog: Following the Federal Dollar, July 7, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/blog/what-can-great-recession-teach-us-about-rent-affordability-age-coronavirus.

Vogell, Heather, with data analysis by Haru Coryne and Ryan Little. "Rent Going Up? One Company’s Algorithm Could Be Why." ProPublica, October 15, 2022. https://www.propublica.org/article/yieldstar-rent-increase-realpage-rent.

Vogell, Heather. "Lawsuit Filed Against RealPage After ProPublica Investigation." ProPublica, October 21, 2022. https://www.propublica.org/article/realpage-accused-of-collusion-in-new-lawsuit.

Weaver, Stephanie. "Renting a Home in US Is Still More Affordable than Owning, New Report Shows." FOX 13 Seattle, January 18, 2024. https://www.fox13seattle.com/news/renting-home-us-still-more-affordable-than-owning-2024-study.

Whitney, Peyton, Alexander Hermann, and Whitney Airgood-Obrycki. "Housing Cost Burdens Climb to Record Levels (Again) in 2023." Housing Perspectives, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, December 3, 2024. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/housing-cost-burdens-climb-record-levels-again-2023.