The AI Advantage: How to Prepare for an Economy That Thinks in Code and Benchmarks in Silence

by Kent O. Bhupathi

When I walked into the TechEx AI & Big Data Expo in Santa Clara last week, I didn’t expect clarity. I expected noise: buzzwords ricocheting off LED screens, startups pitching productivity miracles, enterprise executives nodding sagely to sales demos. And all of that was definitely there. But what stayed with me wasn’t the flash. It was a quieter insight: most professionals aren’t worried that AI will replace them. They’re worried they’re already being measured against it.

The tone of the conversation is shifting.

We’re past the speculative stage. We’re in the age of digital benchmarking, where performance in high-skill jobs is increasingly evaluated in relation to machine-generated baselines. And yet, the labor market remains eerily stable on the surface. So what’s really happening beneath that calm?

Short-Term Story: A Slow Burn, Not a Fire

According to recent empirical studies, the short-term effects of generative AI on employment are surprisingly subdued. A large-scale study in Denmark found that even with widespread adoption of workplace AI chatbots and access to training, there was no significant impact on earnings or recorded hours for workers in AI-exposed roles. Productivity improved incrementally (around 3% on average). But, these gains didn’t translate into labor market upheaval.

AI tools today are primarily being used to support human work rather than to supplant it. About 28% of U.S. workers have adopted generative AI in their jobs, though most use it lightly and occasionally. Tasks such as writing emails, searching for information, or summarizing text are being streamlined, not automated outright. In a customer support case study, novice agents using AI tools improved productivity by 34%, while more experienced agents saw little to no improvement. The technology is raising the floor of performance but has not pushed the ceiling any higher.

This leveling dynamic signals a profound shift in organisational structure. The experience premium, which refers to the slow accumulation of knowledge and intuition that once set veteran employees apart, is showing signs of declining marginal value. As AI tools increasingly function as co-workers, firms must contend with the diminishing relevance of traditional productivity gaps that historically justified promotions, raises and hierarchical authority.

Long-Term Terrain: Uneven, Unforgiving, Unfinished

But the long view is more complex. The IMF estimates that up to 60% of jobs in advanced economies could be meaningfully affected by AI over the next decade or more. That doesn't mean these jobs will vanish. Rather, around half are expected to be augmented by AI, while the rest may undergo significant task substitution.

Some macroeconomic models forecast extreme outcomes. One scenario projects a threefold increase in productivity accompanied by a 23% drop in employment, much of which could unfold within just five years of full-scale AI integration. However, this outcome depends heavily on how quickly industries adapt, whether new types of jobs emerge, and how policy frameworks support or hinder labor mobility.

Historical parallels offer both reassurance and caution. Just as electricity and computers took time to reshape business processes, so too will AI. The difference is speed. Generative AI is spreading faster than past general-purpose technologies, and that pace could compress the learning curve uncomfortably for many workers. The risk is not only in job loss but in falling behind a shifting frontier of relevance.

For Businesses: Rethinking Hierarchies and Incentives

At the expo, one recurring theme was that AI is transforming firms from the inside out. The most immediate change is not job loss. It is the erosion of internal skill hierarchies. AI disproportionately boosts the output of junior or lower-performing employees, compressing performance gaps across the organization. This shift forces companies to rethink how they reward tenure, experience, and informal knowledge networks.

Businesses should ask not how soon they can replace people, but how best to redesign incentives in a more AI-leveraged workforce. The roles most susceptible to transformation are not necessarily the cheapest to automate, but rather the easiest to measure. If your firm is already tracking sales scripts, customer calls, or legal memos, those tasks are next in line for AI integration (regardless of their complexity or strategic value).

Moreover, the deployment of AI tools creates new strategic questions: What does mentorship look like when AI is already coaching junior employees? How do you define excellence when standard tasks are standardized further by machines? These are not hypothetical concerns; they are now live issues for HR departments and executive teams.

For Households: The 30–40% Rule and the Intern Test

For individuals, the key insight is this: AI rarely replaces an entire job. It replaces the most teachable parts. If a smart intern could pick up a third of your responsibilities in a week, that portion of your role is likely exposed. Generative AI thrives on pattern, instruction, and structure. What it struggles with is context, judgment, and intuition.

This aligns with economic research. Most jobs will experience partial task automation rather than complete displacement. Occupations in finance, law, marketing, and software development are already being shaped by AI-generated benchmarks. Performance standards are being subtly recalibrated. Workers in these fields must now act as if their AI-enhanced competitor is already in the room.

The personal responsibility here isn’t just about reskilling. It’s about redesigning your own role in real time by shifting toward responsibilities that are least codifiable. These include unstructured problem-solving, interpersonal negotiation, long-term strategy, and mission alignment. In an AI-rich world, the safest parts of your job are often the hardest to explain.

The Social Stakes: Inequality, Polarization, and Policy

Perhaps the most sobering takeaway is this: AI may equalize performance but does not automatically equalize opportunity. The economic gains are tilting toward capital owners and highly skilled workers who have the tools and flexibility to incorporate AI into their workflows. Wage and wealth inequality may widen rather than shrink.

Demographic effects are already beginning to emerge. Women are more likely than men to hold jobs that involve a high concentration of clerical tasks, which are among the most exposed to AI-driven change. At the same time, younger workers are adopting AI tools more rapidly, whereas many older professionals face challenges in doing so. This disparity increases the chances of early retirement or displacement for those later in their careers.

Policymakers and business leaders must not mistake these early patterns as fixed outcomes. Targeted reskilling, accessible training, and human-centered AI design can mitigate the risks. The question is whether we will act in time.

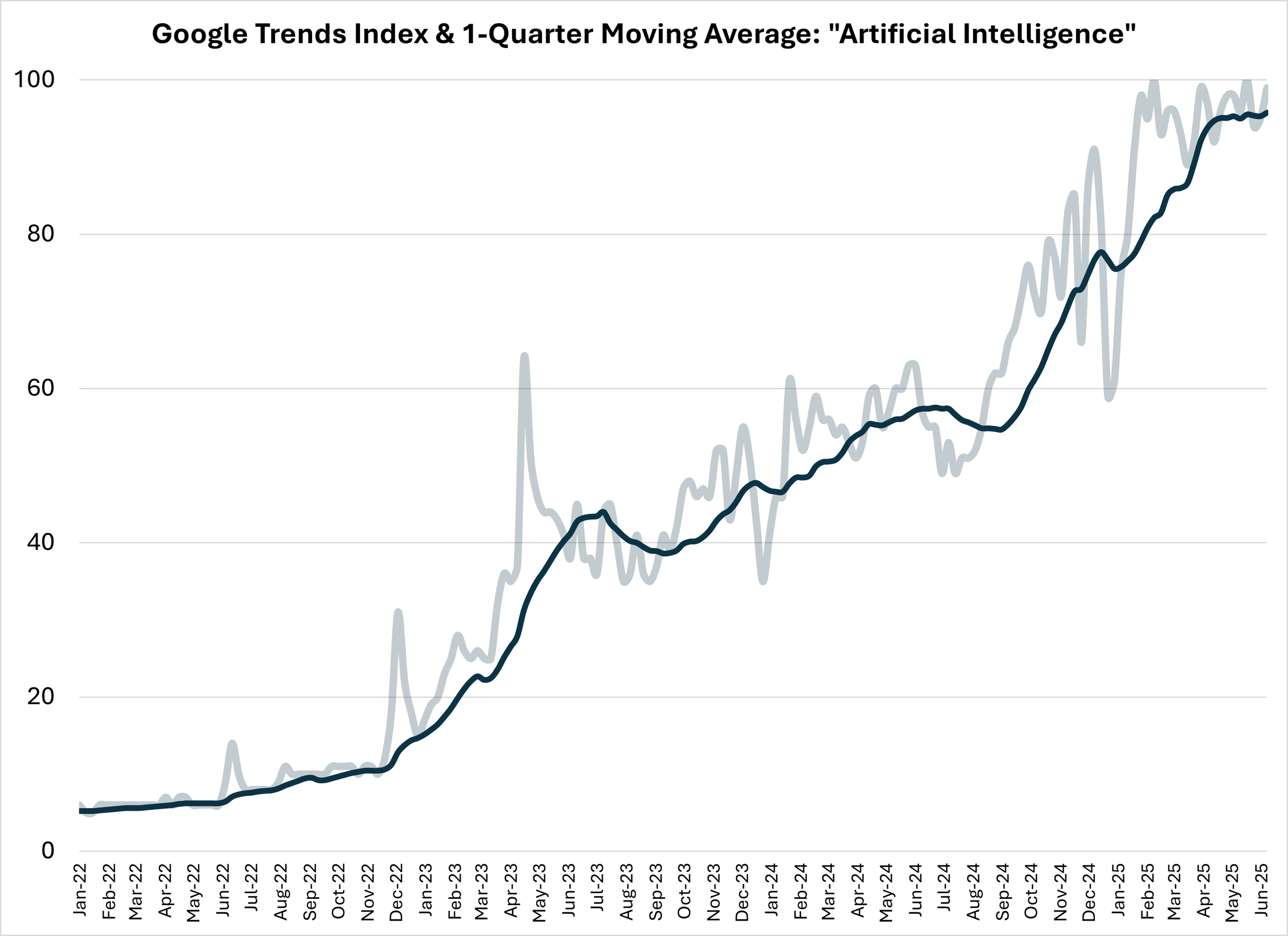

Since January 2023, public interest in artificial intelligence has risen by more than 200 per cent year‑on‑year, signalling a societal fixation of extraordinary velocity. This escalation owes more to narrative momentum than to incremental fundamentals, propelled by compounding innovation, media amplification, and a growing sense of strategic importance. By comparison (and by no means unimpressive) the S&P 500 has produced roughly 16% annualized growth over the same interval, a pace that pales beside the exponential expansion of attention accorded to AI.

Conclusion: Audit the Human

The future of work isn’t a question of survival but of synthesis. Success will belong to those who can blend their uniquely human traits with increasingly capable AI tools. For businesses, this means investing not only in software but in the thoughtful reconfiguration of workflows and incentives. For households, it means evaluating what parts of our labor are durable, not just marketable.

AI is no longer looming on the horizon. It is here, quietly shaping our expectations, altering our benchmarks, and transforming the way value is created and measured. The challenge is not merely to adapt but to discern. What should remain distinctly human in a world that increasingly isn’t?

We must answer that question, not once, but again and again, with every meeting, memo, and milestone. Because what we choose to automate is ultimately a reflection of what we choose to preserve.

Sources:

Acemoglu, Daron. The Simple Macroeconomics of AI. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, May 12, 2024. https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2024-05/The%20Simple%20Macroeconomics%20of%20AI.pdf.

Cazzaniga, Mauro, Florence Jaumotte, Longji Li, Giovanni Melina, Augustus J. Panton, Carlo Pizzinelli, Emma Rockall, and Marina M. Tavares. Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/2024/001. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, January 2024. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/SDN/2024/English/SDNEA2024001.ashx.

Eloundou, Tyna, Pamela Mishkin, Daniel Rock, and Sam Manning. GPTs Are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. NBER Working Paper No. 32966. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2023. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32966.

Georgieva, Kristalina. “AI Will Transform the Global Economy. Let’s Make Sure It Benefits Humanity.” IMF Blog, January 14, 2024. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/01/14/ai-will-transform-the-global-economy-lets-make-sure-it-benefits-humanity.

Huang, Yueling. The Labor Market Impact of Artificial Intelligence: Evidence from US Regions. IMF Working Paper No. 2024/186. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, September 13, 2024. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2024/09/13/The-Labor-Market-Impact-of-Artificial-Intelligence-Evidence-from-US-Regions-554845.

Humlum, Anders, and Emilie Vestergaard. Large Language Models, Small Labor Market Effects. NBER Working Paper No. 33777. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2025. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33777.

Karippacheril, Tina George, Kevwe Pela, and Asbath Alassani. “What We’re Reading about the Age of AI, Jobs, and Inequality.” World Bank Blogs, May 7, 2024. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/jobs/What-we-re-reading-about-the-age-of-AI-jobs-and-inequality.

Kinder, Molly, Xavier de Souza Briggs, Mark Muro, and Sifan Liu. “Generative AI, the American Worker, and the Future of Work.” Brookings Institution, October 10, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/generative-ai-the-american-worker-and-the-future-of-work.

Lynch, Cindy L. 1996. “Facilitating and Assessing Unstructured Problem Solving.” Journal of College Reading and Learning 27, no. 2 (August): 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.1996.10850035.

Muro, Mark, Shriya Methkupally, and Molly Kinder. “The Geography of Generative AI’s Workforce Impacts Will Likely Differ from Those of Previous Technologies.” Brookings Institution, February 19, 2025. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-geography-of-generative-ais-workforce-impacts-will-likely-differ-from-those-of-previous-technologies.

Wang, Ping, and Tsz-Nga Wong. Artificial Intelligence and Technological Unemployment. NBER Working Paper No. 33867. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2025. https://www.nber.org/papers/w33867.

World Bank. Future Jobs: Robots, Artificial Intelligence, and Digital Platforms in East Asia and Pacific. Washington, DC: World Bank, June 2, 2025. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/publication/future-jobs.