Staying the Course: Why the Fed Isn’t Cutting Rates (Yet)

by Kent O. Bhupathi

They never expected to feel stuck in their dream home.

When two dear friends of mine (let’s call them Joe and Jane) bought their two-bedroom starter house in late 2020, it felt like the beginning of a promising chapter. Interest rates hovered just below 4%, their mortgage felt manageable, and with a baby on the way, they believed they were laying down roots. By the start of 2025, the picture had changed. Two children, hybrid jobs pulling them in opposite directions, and no third bedroom in sight. They’d outgrown the house. What they hadn’t outgrown was their 3.5% mortgage.

Each time they browsed listings in nearby school districts, they encountered the same arithmetic. Even a comparable home, with today’s mortgage rates approaching 7%, would push their monthly payments noticeably higher. Technically, they could afford the increase, yet they always decided against putting their house on the market. To them, the cost of moving was a direct cost to their sense of security.

“We’re not living the life we want,” Jane told me, “but we’re not willing to blow up our financial stability just to get a third bedroom.”

Their hesitation is one that echoes across many households. And it’s paired with a question I hear often: If inflation is cooling, why isn’t the Fed cutting interest rates?

It’s a fair question. But behind it lies a widespread misunderstanding of the Federal Reserve’s purpose. The Fed doesn’t exist to make financing easy. Its job is to keep the economy on a steady path. Sometimes that means saying no to short-term relief so that longer-term stability remains achievable.

Two Mandates, One Tough Balancing Act

The Fed has two primary responsibilities: to promote maximum employment and to ensure price stability. These are not just economic targets; they are the foundation for a resilient economy. Right now, both mandates are in a delicate state of transition.

Over the past year, inflation has declined sharply from its 2022 peak. Headline inflation, once close to 9%, has cooled to roughly 2 to 3%. Core inflation, the metric favored by the Fed, now sits near 2.5%. Meanwhile, unemployment remains in-line with historical lows at about 4.2%.

This is what economists call a "soft landing": a situation where inflation is brought under control without triggering mass layoffs or a deep recession. It’s a rare and fragile achievement. And the Fed is not eager to jeopardize it.

(The Honest Economist’s more robust recession measure indicates that US households remain in a rather delicate financial position, notwithstanding the reassuring headline indicators)

Why Holding Steady Is a Strategy, Not Inaction

It may seem logical to cut rates now that inflation has cooled. But several reasons explain why the Fed is holding steady instead.

First, core inflation is still slightly above target. The Fed wants to see sustained progress before declaring victory. A premature rate cut could reverse disinflation gains by reigniting demand in sensitive sectors like housing and autos.

Second, public expectations about inflation remain stable. Market-based measures, such as Treasury breakeven rates, suggest that investors believe the Fed will keep inflation around 2% over the long run. That credibility is hard-won and easy to lose. Cutting too soon could send the wrong signal.

And finally, we’ve been here before. In the 1970s, the Fed eased too quickly after an initial bout of inflation. The result was a second wave of even higher inflation and a much harsher policy response later. Today’s Fed leadership has made clear that it will not repeat that mistake.

The Uneven Impact of Higher Rates

That said, the consequences of holding rates high are not felt equally.

Across my network, I’m hearing a wide range of strategies and adjustments from both households and businesses. People are adapting, sometimes painfully, to the new reality.

For households, the cost of borrowing, particularly for mortgages, has created a kind of inertia. Many existing homeowners, like Joe and Jane, are locked into low-rate loans from 2020 or 2021. According to recent Fed data over 80% of mortgage borrowers still pay under 5%. This has shielded them from payment shocks but it also discourages mobility, making it harder for growing families or relocating workers to move.

Meanwhile, first-time buyers face much steeper hurdles. Mortgage payments on a median home have risen by hundreds of dollars per month compared to just a few years ago. In many cases, this has priced families out of the market entirely.

Outside the housing sector I have observed households respond in creative ways. Some are directing their expenditure towards categories where prices have moderated, such as used vehicles and durable goods. Others are reconsidering their career trajectories internally, pursuing promotions or new roles within their current organizations rather than changing employers in a now-cooled labor market. I have also noted renewed interest in cooperative financial models, including community buying groups and shared energy projects, which help families stretch their budgets.

How Businesses Are Navigating the Same Terrain

In the business world, too, I’ve observed an interesting shift.

Some firms are exploiting a less fluid labour market. With job-switching on the wane after the Great Resignation, employers are finding opportunities to attract high-value talent by offering modest incentives such as slightly higher wages, improved flexibility or other non-monetary benefits.

Others are locking in long-term contracts with suppliers, taking advantage of price stabilization in the wake of supply chain normalization. These businesses are betting that locking in today’s rates might buffer them from potential volatility later.

Inventory strategy is another area of change. As consumer demand softens, several firms are leaning into leaner, just-in-time inventory models to avoid overstocking if the economy slows further.

What connects all of these approaches is a mindset of prudence. Businesses are not panicking; they are preparing.

The Pressure to “Do Something”

Still, the political and emotional pressure on the Fed to cut rates is growing. Consumer sentiment remains low, despite the improvements in inflation data. Essentials like rent, groceries, and utility bills are still expensive, and for many households, real income gains have only recently begun to catch up with pandemic-era price spikes.

It is tempting to blame interest rates, given that they are the most visible instrument at the Fed’s disposal. Yet many of the price pressures consumers encounter, particularly in sectors such as housing or food, originate in long-standing structural issues.

Cutting rates now might ease the cost of borrowing in the short term. Yet, in a geopolitical landscape that continually generates new disruptions, such a move, if premature, could just as readily rekindle a destabilizing inflation. That is a gamble the Fed seems unwilling to take.

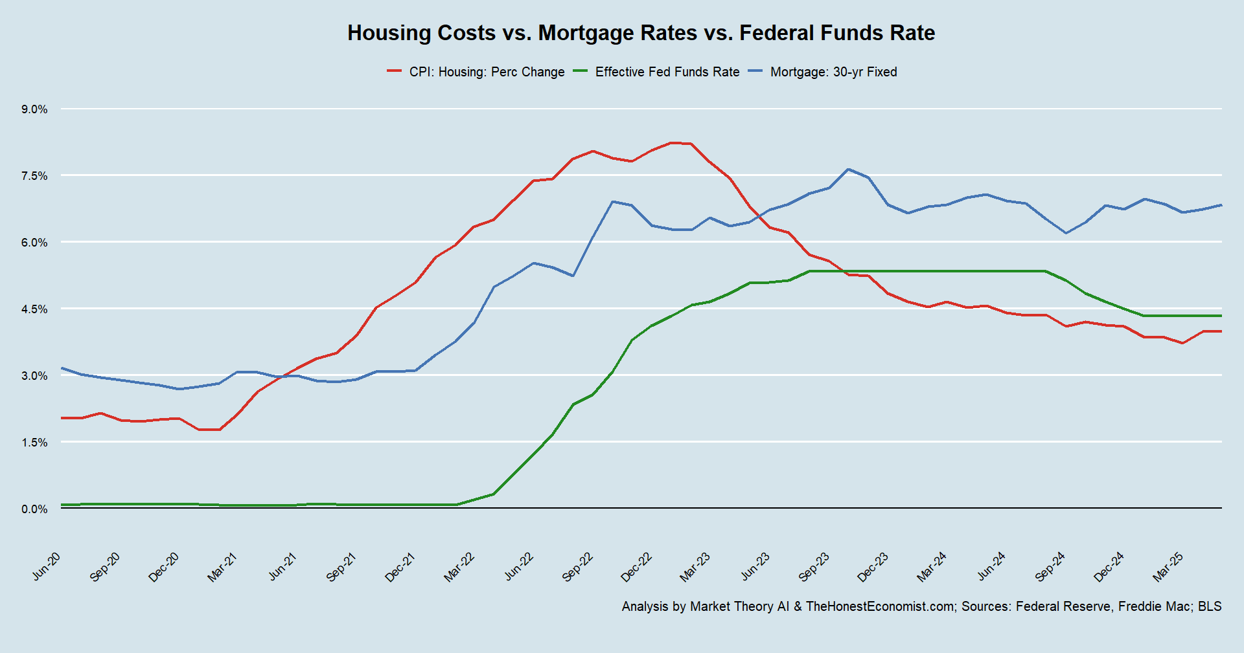

Housing inflation accelerated from early-2021 and peaked near 8% in mid-2022, whereas the 30-year mortgage rate began climbing only after markets anticipated monetary tightening late in 2021. The Federal Reserve maintained the policy rate at the zero lower bound until March-2022 and then lifted it swiftly to roughly 5% by mid-2023. The sequence of events, with housing inflation rising first, mortgage rates adjusting next, and the federal funds rate responding last, signals a reactive policy stance and underscores the lag between a policy move and its effect on retail borrowing costs and, in turn, shelter prices. By early-2025, two of the three series have converged in the 4 to 5% range, suggesting partial normalization; however, mortgage rates still exceed the policy rate, a spread that reflects an elevated term premium and persistent credit-risk aversion, both of which continue to curb housing affordability despite easing measured inflation.

A Matter of Risk Management

From a policy standpoint, the choice to pause rate cuts is about risk management. Markets are signaling that inflation is likely to continue easing, and that rate cuts may be appropriate later in the year. But the Fed has made clear that it will respond to data, not forecasts.

And the risks are asymmetric. If the Fed waits too long to cut, it can always lower rates later. But if it cuts too early and inflation rebounds, it could lose hard-won progress and be forced to tighten again at even greater cost.

This cautious stance is echoed in the Fed’s own projections. The June 2025 Summary of Economic Projections suggests only modest rate cuts later this year, and even those are contingent on inflation continuing to fall.

Conclusion: A Longer View of Stability

Joe and Jane still have not sold their house. Nevertheless, they are making do, and they are not alone. Across the country households and businesses are adapting in smart, measured ways as they seek a balance between caution and forward motion.

For all its complexity, the Federal Reserve’s job comes down to this: to ensure that the path ahead is smoother than the path behind. Sometimes that means holding steady when the pressure is loudest to move.

The rate pause we’re living through is not a refusal to act; it is an act of restraint. A choice to stay vigilant. And while it may not offer the short-term relief many hope for, it is laying the groundwork for something more lasting: an economy where prices are stable, jobs are secure, and the cost of living no longer outpaces the lives we want to build.

Sources:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Monetary Policy Report: Report to Congress, June 2025. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve, June 20, 2025. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/20250620_mprfullreport.pdf.

Daly, Mary C. "Landing Softly Is Just the Beginning." FRBSF Economic Letter, no. 2024-28, October 21, 2024. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/2024/10/landing-softly-is-just-the-beginning/.

Deng, Yayue, Mohan Xu, and Yao Tang. "FMPAF: How Do Fed Chairs Affect the Financial Market? A Fine-Grained Monetary Policy Analysis Framework on Their Language." arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06115, March 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.06115.

English, William B., Brian Sack, Charles L. Evans, Christina D. Romer, and David H. Romer. "Symposium on the Federal Reserve’s Monetary Policy Framework Review." Brookings Institution, September 25, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-federal-reserves-monetary-policy-framework-review/.

Haughwout, Andrew, Donghoon Lee, Daniel Mangrum, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw. "Income Growth Outpaces Household Borrowing." Liberty Street Economics (blog), Federal Reserve Bank of New York, November 13, 2024. https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/11/income-growth-outpaces-household-borrowing/.

McGeever, Jamie. "Optimal Fed Response to Tariffs? Ease Policy: McGeever." Reuters, April 3, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/optimal-fed-response-tariffs-ease-policy-mcgeever-2025-04-02/.

Rugaber, Christopher. "Consumer Sentiment Rises for First Time in 2025 as Inflation Remains Tame." PBS NewsHour, June 13, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/consumer-sentiment-rises-for-first-time-in-2025-as-inflation-remains-tame.

Schneider, Howard, and Ann Saphir. "Fed Keeps Rates Steady but Pencils in Two Cuts by End of 2025; Powell Sees 'Meaningful' Inflation Ahead." Reuters, June 18, 2025. Updated June 19, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/fed-set-hold-rates-steady-middle-east-crisis-tariffs-cloud-outlook-2025-06-18/.

Schulze, Jeffrey, and Josh Jamner. "AOR Update: Wage Moderation Allows Fed Patience." Franklin Templeton, May 7, 2024. https://www.franklintempleton.ca/en-ca/articles/2024/clearbridge-investments/aor-update-wage-moderation-allows-fed-patience.

University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. "Consumer Sentiment Drops as Inflation Worries Escalate." Surveys of Consumers, February 21, 2025. https://isr.umich.edu/news-events/news-releases/consumer-sentiment-drops-as-inflation-worries-escalate/.