Leave the Chantilly Alone! The Quiet Rewriting of America’s Consumer Experience

by Kent O. Bhupathi

At first, I laughed.

The idea that a grocery store cake could spark a viral meltdown felt like classic internet absurdity. When I read that Whole Foods had quietly altered the recipe of its beloved Berry Chantilly cake, I chuckled at the idea of social media users crying betrayal over a dessert.

Almost immediately, though, I felt something else: inspired. The public outcry worked! Faced with customer backlash, Whole Foods reversed course and reintroduced the original recipe. A multibillion-dollar enterprise had changed direction, not because of lawsuits or legislation, but because regular people noticed a change they weren’t okay with and refused to let it slide. That’s no small thing.

But then, I got annoyed.

For this wasn’t just about cake. It wasn’t even just about Whole Foods. Rather, it offers a glimpse into how even the most well-resourced firms quietly probe the limits of what they can impose on consumers. Instead of increasing prices outright, they shrink portions, substitute ingredients and skimp on quality. In this case, the shelf price stayed fixed despite higher berry costs and stronger demand; the company simply degraded the recipe and counted on customers failing to notice.

True, that episode happened a while back. But with food prices rising again since February, and market concentration in consumer sectors increasing by more than 2% annually, I do not believe the story to have lost its relevance. In fact, it’s more urgent now. It captures something fundamental about where the U.S. economy is heading: not just toward higher costs, but toward lower quality, obscured by opacity.

This is a different kind of inflation. It’s not just about the number on the receipt. It’s about the value we actually receive in return. It’s about paying the same for a little less joy, a little less substance, and a little less trust.

As the U.S. economy continues to move beyond the pandemic-era inflation spike, our national conversation is overdue for a shift. From how high prices have climbed to how much value quietly disappears with each transaction. From inflation as a macroeconomic metric to inflation as a lived experience. Often subtle, sometimes sneaky, and deeply human.

The Shift from Price Tags to Package Integrity

Since 2021, Americans have faced not only high inflation but also two subtler forces: shrinkflation, where product sizes or quantities decrease without a nominal price drop, and skimpflation, where quality or service declines without a discount. These are not just corporate quirks. They are structural responses to market power and consumer psychology.

Shrinkflation is measured by agencies like the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which adjusts price indices to reflect unit costs. A cereal box shrinking from 18 oz to 16 oz without a price change gets recorded as a price hike. But many consumers don’t notice. They just feel that their money doesn’t go as far. Skimpflation is even murkier: hotels skipping room cleanings, restaurants using cheaper oils, or stores replacing fresh with pre-packaged goods.

A 2024 review of scanner data found 1.9% of products downsized in the last decade, and downsizing occurred five times more often than upsizing. Most of these products saw no price cut, meaning unit prices rose quite subtlety. Skimpflation, though harder to track in aggregate, is widely reported in service industries and branded goods.

These shifts point to a deeper issue: consumers are increasingly getting less for more, and it’s happening in ways that official inflation statistics struggle to capture.

Market Power Behind the Disguised Price Hikes

A major reason firms can shrink or skimp without immediate consequences lies in market concentration.

In less competitive markets, companies can raise effective prices by reducing quantity or quality, rather than changing the sticker price. The Economic Policy Institute found that rising profit margins, not just input costs, explained over 40% of price hikes in early post-pandemic recovery years. Much of this was enabled by dominant firms operating in sectors with few alternatives.

Diapers provide a vivid example: two firms command roughly 70% of the United States market, and between 2019 and 2023 retail prices climbed by more than 30% even as input costs fell in the latter year. Rather than pass on the savings, these manufacturers relied on brand loyalty and limited rivalry to safeguard their margins; their market power lets them exploit price stickiness and introduce shrinkflation or skimpflation with little risk of customer defection. Senior executives seldom admit such tactics in unvarnished terms, yet several have acknowledged during earnings calls that “price pack architecture”, a regular euphemism for shrinkflation nowadays, contributed as much as 20% to effective price increases.

And this dynamic is amplified by vertical integration and brand recognition. Large firms have the ability to retool packaging and distribution at scale. Smaller businesses often can’t afford to play the same game. So, the companies best positioned to resist cost hikes are also the most likely to engage in deceptive pricing strategies.

The Psychology of Not Noticing

Even when the changes are noticeable, many consumers don’t react. That’s because these pricing tactics exploit informational asymmetry and cognitive bias.

Behavioral economics tells us that people tend to focus on the total price, not the unit price. A study of McCormick’s black pepper tins found the weight dropped from 4 oz to 3 oz, but consumers hardly noticed. Sales stayed steady, even as the per-ounce cost jumped. Researchers estimate the brand would have lost up to 8% market share had all consumers been fully aware.

This is why companies go to great lengths to avoid overt price hikes. They’ll redesign containers, adjust labeling, or tweak recipes just enough to preserve the illusion of continuity. The goal is to stay under the radar. When price goes up, consumers reconsider. When size shrinks, they often don’t.

Skimpflation adds another layer: it relies on degraded experiences that are harder to track. A sauce tastes slightly off. A roll of toilet paper feels just a bit thinner. A flight feels a bit less civilized. But unless consumers are vigilant, the pattern doesn’t register as inflation. It just feels like the world is getting worse.

Shrinkflation and Skimpflation as Structural Phenomena

While shrinkflation alone is far from the primary driver of food-at-home inflation, its symbolic significance is far greater. It reveals how companies exercise power in markets where competition fails to discipline pricing. The practice thrives not only because of rising costs, but because of strategic inattention by both by consumers and regulators.

Research shows that consumers view shrinkflation and skimpflation as more unfair than traditional price hikes. Why? Because they feel deceived. A Marketing Science study found that transparency helps: when downsizing is clearly explained, consumer trust is less likely to erode. But most firms don’t explain. They rely on obfuscation, betting that the average shopper won’t notice until it's too late.

The result is a subtle rewriting of the social contract. If companies can consistently deliver less without being held accountable, the consumer economy becomes less about choice and more about endurance. And unless markets are made more competitive, these tactics will likely persist even as inflation cools.

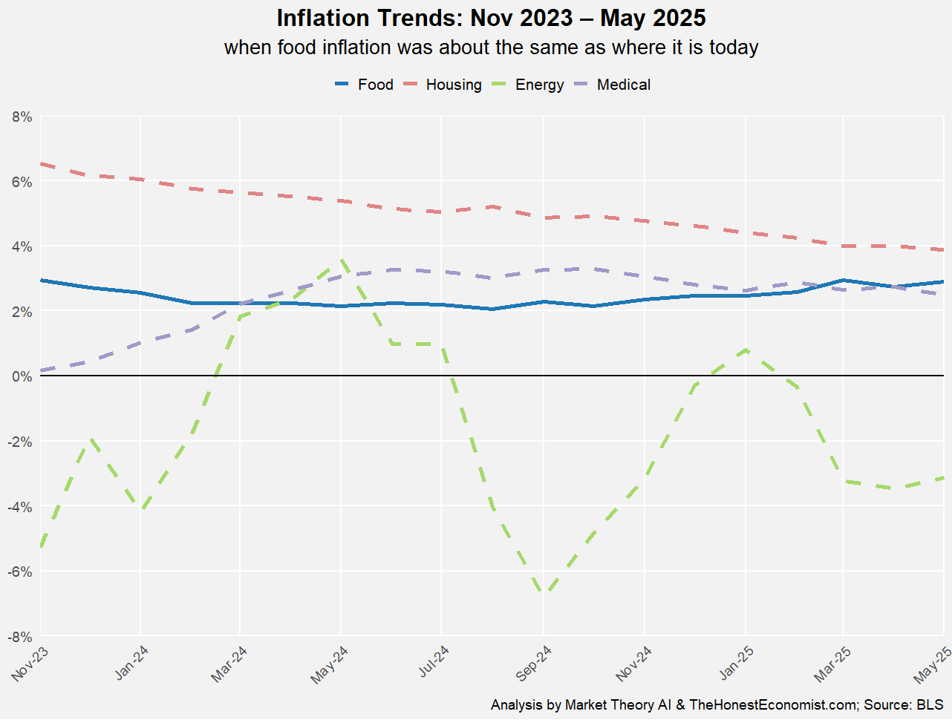

Since the start of 2025, food inflation is the only major spending category that has continued to climb, with the pace of increase itself edging higher, whereas housing, medical and energy costs have either levelled out or declined. Housing inflation, although still elevated, has trended lower in line with a cooling rental market; medical inflation rose briefly in mid-2024 before flattening; and energy prices have remained erratic, shifting between sizeable deflationary dips and short-lived rebounds driven by global and seasonal forces. The persistence and recent acceleration of food prices therefore help explain why households still feel the pinch even as headline measures of inflation show signs of easing.

How Consumers Are Fighting Back

Still, people are learning to push back. In households across the country, five practical strategies are emerging:

Track Unit Pricing Rigorously: By comparing price per ounce, sheet, or serving, consumers can uncover hidden downsizing, even when packaging looks identical.

Leverage Community Intelligence: Platforms like Reddit (e.g., r/shrinkflation) and TikTok are becoming consumer watchdogs, publicly exposing brand behavior in real time.

Write Directly to Brands and Retailers: As the Chantilly Cake saga proved, coordinated feedback can work. Brands fear reputational damage, especially when loyal customers speak up.

Stockpile Non-Perishables When Pricing Is Rational: Buying in bulk during deals helps avoid future inflation cycles and sidestep shrinkflation entirely.

Use Price-Tracking Apps: Tools like Basket and CamelCamelCamel reveal price history and packaging changes, helping shoppers make more informed decisions.

Conclusion: Inflation as a Lived Experience

Although shrinkflation can bolster quarterly earnings, it risks hollowing out what matters most: trust. Nearly 50% of United States shoppers say they would abandon a product after realising it has been quietly downsized, and more than 70% admit they would never return once they have discovered a suitable alternative. This erosion of loyalty represents a hidden cost that compound interest cannot offset. Yet companies need not face an inevitable backlash. Clear explanations of rising input costs, the option of a premium line that upholds original standards, or a family-size package that preserves value all help to preserve goodwill.

Inflation, then, is more than a statistic; it is a day-to-day encounter negotiated at the checkout, shaped as much by corporate strategy as by macroeconomic forces. Consumers are not merely paying more. They are confronting the uneasy sense that they are receiving less and that the social contract between buyer and seller has been unilaterally revised. Whole Foods may have restored its Berry Chantilly cake to its former glory, yet the larger marketplace remains unsettled.

Ensuring that a pound still feels like it buys a pound’s worth of value ought to be the baseline for civil commerce. In the current environment, however, such an assurance takes on a quietly radical character. Firms that meet this expectation forthrightly will not only safeguard margins in the long run; they will also help stabilize a public mood increasingly wary of clever packaging and covert cost-cutting.

Sources:

Bennett, Jeannette. "Beyond Inflation Numbers: Shrinkflation and Skimpflation." Page One Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 1, 2022. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/page-one-economics/2022/12/01/beyond-inflation-numbers-shrinkflation-and-skimpflation.

Bivens, Josh. "Profits and Price Inflation Are Indeed Linked." Working Economics Blog, Economic Policy Institute, September 5, 2024. https://www.epi.org/blog/profits-and-price-inflation-are-indeed-linked/.

Bourne, Ryan, and Jai Kedia. "New BLS Data Confirms Shrinkflation Is a False Panic." Cato Institute, June 24, 2024. https://www.cato.org/commentary/new-bls-data-confirms-shrinkflation-false-panic.

Bräuning, Falk, José L. Fillat, and Gustavo Joaquim. Cost-Price Relationships in a Concentrated Economy. Current Policy Perspectives, 2022 Series. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2022. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2022/cost-price-relationships-in-a-concentrated-economy.aspx.

Chalioti, Evangelia, and Konstantinos Serfes. "Shrinkflation." Economics Letters 234 (2024): 111959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2024.111959.

Daily, Ryan. "Shrinkflation-Weary Consumers Turn to Private Label." FoodNavigator-USA, April 7, 2023. https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2023/04/07/shrinkflation-weary-consumers-turn-to-private-label/.

Doris, Áine. "Do Shoppers Notice Shrinkflation?" Chicago Booth Review, December 5, 2024. https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/do-shoppers-notice-shrinkflation.

Evangelidis, Ioannis. "Shrinkflation Aversion: When and Why Product Size Decreases Are Seen as More Unfair than Equivalent Price Increases." Marketing Science 43, no. 2 (2024): 280–288. https://ideas.repec.org/a/inm/ormksc/v43y2024i2p280-288.html.

Evangelidis, Ioannis. Skimpflation Outrage: Decreases in Product Quality Are Seen as Much More Unfair Than Decreases in Size and Increases in Price. Marketing Science Institute Working Paper Series 2024, Report No. 24-107. https://thearf-org-unified-admin.s3.amazonaws.com/MSI_Report_24-107.pdf.

Janssen, Aljoscha, and Johannes Kasinger. Shrinkflation and Consumer Demand. Kilts Center at Chicago Booth Marketing Data Center Paper. Last revised March 17, 2025. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4783491.

Kalaitzandonakes, Maria, Jonathan Coppess, and Brenna Ellison. "The Price Is Right? Consumer Preferences for Food Manufacturer Responses to Increased Input Costs." farmdoc daily 14, no. 117 (June 24, 2024). https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2024/06/the-price-is-right-consumer-preferences-for-food-manufacturer-responses-to-increased-input-costs.html.

Owens, Lindsay, Ph.D. Big Profits in Small Packages. Groundwork Collaborative, March 6, 2024. https://groundworkcollaborative.org/work/big-profits-in-small-packages/.

Pilat, Kasia, and Alexa Weibel. "Whole Foods Tried to Change This Cake Recipe. Customers Lost It." The New York Times, October 2, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/02/dining/whole-foods-berry-chantilly-cake.html.

Rebelo, Sergio, Miguel Santana, and Pedro Teles. Behavioral Sticky Prices. NBER Working Paper No. 32214. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2024, revised November 2024. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32214.