Tariffs, Tactics, and Trade-offs: How Our Current Trade War Strategy Misses the Long Game

by Kent O. Bhupathi

In early 2024, a friend of mine (let’s call her Jane) launched a skincare startup with a mission that was equal parts personal and global. Her serums blended botanical oils from Southeast Asia with rare extracts from Latin America, promising customers something fresh, clean, and effective.

By mid-year, boutique retailers had taken notice. Online orders were ticking upward. She was finally seeing the promise of her idea come to life until a spreadsheet of customs estimates landed in her inbox. A critical ingredient, once affordable, now carried a tariff surcharge in excess of 100%. Essentially, Jane’s next shipment would cost more in tariffs than the goods themselves.

"I have months' worth of inventory stranded abroad," she told me. "When that's gone, I don't know what happens."

Jane's business is just one of many caught in the crossfire of a trade strategy that seems more focused on making headlines than building sustainable deals.

This story is not isolated. It is the logical endpoint of a negotiation framework that has prioritized pressure over patience and performance over process.

The 90-Day Deadline That Came and Went

Today marks the expiration of yet another self-imposed trade negotiation deadline. This one was announced in the spring of 2025.

Originally framed as a strategic pivot to get “tough" on partners like Japan, South Korea, and Mexico, the deadline came with a set of veiled threats: raise tariffs unilaterally unless new concessions were extracted quickly.

But the deadline has come and gone with little substance to show. In its stead, the administration wishes to circulate a succession of terse, reproachful letters that operate more as muted ultimatums than genuine diplomatic engagement. These gestures act as pressure valves, delaying hikes while keeping tension high. The cycle repeats: threaten, delay, extract. It may generate headlines, but it doesn't generate durable agreements.

This is not how multinational deals are made. Real trade negotiations take time, expertise, consensus-building, and policy coordination. Compressing them into arbitrary timelines undermines outcomes and erodes credibility. Worse, it turns the lives of people like my friend Jane into collateral damage.

The Economic Costs Beneath the Surface

To fully grasp what’s at stake, we have to look beyond headlines and deadlines. An ever-growing and increasingly cohesive body of research from across the economic sciences reveals that the long-run implications of recent U.S. tariff policies are far more damaging than political talking points suggest.

Consumer and Business Costs. Tariffs imposed since 2018 raised import prices almost one for one with the tariff rate. Foreign exporters refused to absorb the cost, passing it on to U.S. consumers and importers. By late 2018, U.S. firms and households were paying an extra $1.4 billion each month because of these duties. For the average household, the annual burden rose from about $419 in 2018 to as much as $800 by mid-2019. A vivid example is the 20–50 % tariffs on imported washing machines, which increased retail prices by around 12%, adding roughly $86 per washer and $92 per dryer, even though dryers were not directly tariffed (this is known as “derived demand”). The estimated consumer cost of this single measure approached $1.5 billion a year.

Input Costs and Domestic Competitiveness. Many U.S. manufacturers depend on imported intermediate goods such as steel, aluminium, electronic components, and a great deal more. Tariffs on these inputs raised costs for downstream producers, pushing up factory gate prices and squeezing margins. Larger companies were often able to adjust, but small and mid-sized manufacturers faced stark choices: cut wages, delay investment, raise prices, scale down, or shut down. Studies confirm that these firms absorbed tens of billions of dollars in tariff-related costs. By 2025, U.S. companies had collectively shouldered about $46 billion in direct tariff liabilities from 2018–2019 alone.

GDP and Welfare Effects. In macroeconomic terms, the effect on GDP was modest yet measurable. Moody’s Analytics estimated a 0.3% loss in real GDP and 300,000 fewer jobs by late 2019. Other studies placed the decline nearer 0.7%. The National Bureau of Economic Research calculated an annual net welfare loss of roughly $25–30 billion, about 0.13% of GDP, once tariff revenue and gains to domestic producers were included. U.S. consumers and firms forfeited around $114.2 billion a year through higher costs while the federal government collected about $65 billion in duties. Protectionism, in short, reduced the size of the economic pie.

Additionally, these findings provide yet another reason why measuring recessions solely through headline GDP can lead business leaders and policymakers astray. There is fortunately a more robust alternative!

Employment Effects. Although tariffs were intended to safeguard employment, the net result skewed negative. A Federal Reserve study found that manufacturing industries exposed to the duties lost jobs because input costs rose and exports fell. A few thousand positions were preserved in sectors like steel and appliance production, but they came at an exorbitant price, in some instances exceeding $800,000 for each job. Steel-consuming industries, which employ far more workers, faced higher prices and trimmed payrolls. Agriculture, especially export-oriented crops such as soybeans and pork, suffered acutely. And China’s retaliation wiped out a $24 billion export market, prompting the United States to provide $28 billion in emergency aid to farmers. Even with that support, bankruptcies increased and many small farms failed.

Geographic and Distributional Impact. The burdens were unevenly distributed. Research by Fajgelbaum et al. shows that pro-tariff regions, particularly rural and farm-heavy Midwestern states, bore the brunt of retaliatory measures. Politically sensitive manufacturing counties in swing states received only limited protection. Lower-income households nationwide felt the squeeze more sharply because tariffs worked as a regressive tax on everyday items such as electronics, clothing and household appliances.

Investment and Supply Chains. Trade uncertainty prompted a marked pull-back in business investment during 2019. Firms shelved expansion plans while debating which suppliers would become prohibitively expensive. Some redirected sourcing from China to third countries such as Vietnam or Mexico, yet this diversion rarely narrowed the overall deficit. Bilateral trade with China contracted, but the broader U.S. external gap stayed largely unchanged. Smaller firms, lacking the scale to relocate production, either absorbed the extra costs or exited the market.

Long-Term Competitiveness. In the longer term, competitiveness deteriorated in select sectors. Labor productivity in U.S. steel, for example, fell by roughly 32% between 2017 and 2023, whereas GDP-based productivity in the wider economy rose by 15%. With weaker competitive pressure, firms delayed innovation and efficiency gains. Downstream industries, which rely on affordable inputs, became less able to compete internationally.

Taken together, these effects offer a clear verdict. The tariffs dented national GDP only slightly but they inflicted concentrated, persistent harm on households, small businesses, and regional economies that depend on global trade.

Tactics Over Strategy: A Playbook Misaligned

The failure to produce meaningful trade gains by the 90-day deadline is not just a story of delays. It is a story of design flaws. Drawing from Craig VanGrasstek’s Trade Negotiations Training Manual, we see clear departures from the foundational principles of successful diplomacy.

Since re-entering office in 2025, the current administration has leaned heavily on headline tactics. These include issuing tariff threats with little warning, pursuing time-limited pressure campaigns, and operating through executive orders instead of structured policy processes. The administration has bypassed multilateral forums like the World Trade Organization, sidelined congressional input, and weakened internal institutional coordination. Negotiations are treated as sprints rather than marathons. Legislative buy-in, regulatory planning, and long-term enforcement mechanisms are treated as secondary to public performance.

This approach has real consequences. Countries such as Canada, Japan, and members of the European Union have responded with retaliatory tariffs, turning potential allies into cautious skeptics. Deal scopes have remained narrow, transactional, and focused on imposing unilateral gains rather than building mutual progress.

Even when the United States has secured agreements, such as with the United Kingdom or Vietnam, they have come without structural reforms or broad economic alignment. These are not comprehensive trade agreements. They are temporary releases of pressure. They lack the policy architecture to support long-term success.

Shrinkflation and Skimpflation as Structural Phenomena

While shrinkflation alone is far from the primary driver of food-at-home inflation, its symbolic significance is far greater. It reveals how companies exercise power in markets where competition fails to discipline pricing. The practice thrives not only because of rising costs, but because of strategic inattention by both by consumers and regulators.

Research shows that consumers view shrinkflation and skimpflation as more unfair than traditional price hikes. Why? Because they feel deceived. A Marketing Science study found that transparency helps: when downsizing is clearly explained, consumer trust is less likely to erode. But most firms don’t explain. They rely on obfuscation, betting that the average shopper won’t notice until it's too late.

The result is a subtle rewriting of the social contract. If companies can consistently deliver less without being held accountable, the consumer economy becomes less about choice and more about endurance. And unless markets are made more competitive, these tactics will likely persist even as inflation cools.

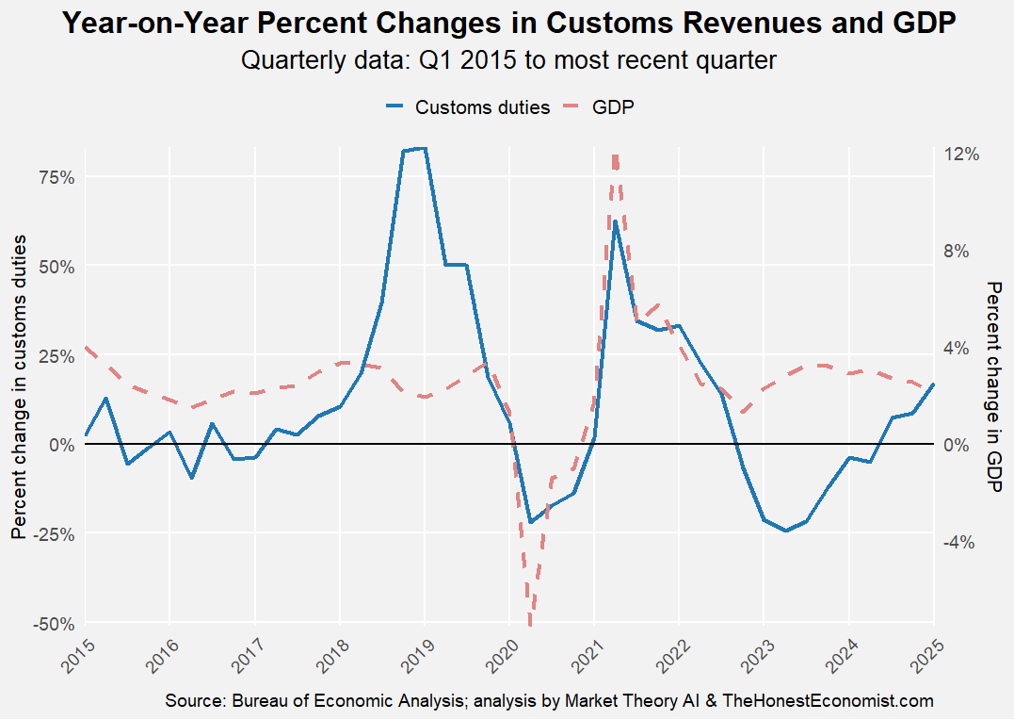

The chart traces quarterly year-on-year movements in United States customs duty revenues alongside real GDP growth from 2015 to the latest quarter, revealing that tariff-driven receipts and overall economic output do not follow a one-for-one trajectory. Crucially, the most recent two-year window underscores an inverse pattern: as GDP settles into moderate yet steady expansion, duty revenues slip into negative territory before only modestly recovering, signaling that softer import volumes and the fading of tariff-base effects can depress fiscal inflows even while the broader economy grows. The overall picture affirms that customs duty changes respond to trade policy and import dynamics rather than mirroring aggregate output.

Conclusion: Rebuilding Credibility and Centering People

If the past ten years have taught us anything, it is that trade policy is not just about nations negotiating. It is about people living with the consequences. We need a better way forward. That starts by rebuilding the credibility that years of theatrical tactics have started to erode.

Constructive trade agreements are built through methodical sequencing, broad stakeholder engagement, and long-term strategic vision. Successful negotiators identify the Zone of Possible Agreement, align domestic institutions, and define enforcement pathways early. They balance sectoral priorities with national interests and frame deals within regional and multilateral contexts to amplify leverage.

There are also diplomatic opportunities that have gone untapped. Joint standards on digital trade, climate-linked tariffs, and collaborative enforcement on labor standards offer common ground where the United States could lead through example and partnership, rather than pressure.

Most importantly, future trade policy must begin by centering the real people impacted by it. The entrepreneur navigating a shattered supply chain. The factory worker whose shift was canceled. The household budgeting against higher grocery bills. These are not collateral. They are the real economy.

Jane is now considering moving abroad with her husband to restart her business in a market less prone to disruption. "When what I have is out, it is likely to stay that way for a long time," she said. The irony is sharp. A U.S. trade policy meant to protect American entrepreneurs is pushing them away.

Trade is not just about numbers on a balance sheet. It is about trust, time, and the texture of everyday economic life. If we want policy to serve people rather than platforms, we have to stop treating negotiation like a stage and start treating it like a strategy. The 90 days are up. But that does not mean we are out of time. It means we need to start using it differently.

Sources:

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David E. Weinstein. “New China Tariffs Increase Costs to U.S. Households.” Liberty Street Economics (blog), Federal Reserve Bank of New York, May 23, 2019. https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/05/new-china-tariffs-increase-costs-to-us-households/.

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David E. Weinstein. “The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 4 (Fall 2019): 187–210. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.33.4.187.

Bade, Gavin, and Brian Schwartz. “Trump Said Trade Deals Would Come Easy. Japan Is Proving Him Wrong.” Wall Street Journal, July 2, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/economy/trade/trump-trade-tariff-deal-japan-c87ee950.

Denham, Barbara Byrne. “Lower-Income States and Metros Face the Greatest Burden from Impending Tariffs.” Oxford Economics (blog), February 12, 2025. https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/lower-income-states-and-metros-face-the-greatest-burden-from-impending-tariffs/.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo D., Penny Goldberg, Patrick Kennedy, and Amit K. Khandelwal. “The Return to Protectionism.” Microeconomic Insights, December 2, 2020. https://microeconomicinsights.org/the-return-to-protectionism/.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo, and Amit Khandelwal. The Economic Impacts of the US–China Trade War. NBER Working Paper No. 29315. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2021. Revised December 2021. https://www.nber.org/papers/w29315.

Fettig, David. “What Washing Machines Can Teach Us about the Cost of Tariffs.” UChicago News, University of Chicago, April 22, 2019. https://news.uchicago.edu/story/what-washing-machines-can-teach-us-about-cost-tariffs.

Flaaen, Aaron, and Justin Pierce. Disentangling the Effects of the 2018–2019 Tariffs on a Globally Connected U.S. Manufacturing Sector. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-086. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 23, 2019. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2019086pap.pdf.

Fleisher, Chris. “The Spillover Effects of Trade Wars.” AEA Research Highlights, American Economic Association, July 31, 2020. https://www.aeaweb.org/research/washing-machines-2018-tariffs-effect.

Hass, Ryan, and Abraham Denmark. “More Pain than Gain: How the US–China Trade War Hurt America.” Brookings Institution, August 7, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/more-pain-than-gain-how-the-us-china-trade-war-hurt-america/.

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde. “Trump’s Tariffs Enrich Steel Barons at High Cost to US Manufacturers and Households.” RealTime Economics (blog), Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 2, 2025. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/trumps-tariffs-enrich-steel-barons-high-cost-us-manufacturers-and.

Javorcik, Beata, Katherine Stapleton, Benjamin Kett, and Layla O’Kane. “Did the 2018 Trade War Improve Job Opportunities for US Workers?” Research Briefs in Economic Policy, no. 362, Cato Institute, December 13, 2023. https://www.cato.org/research-briefs-economic-policy/did-2018-trade-war-improve-job-opportunities-us-workers.

Russ, Kadee. “The Costs of U.S. Tariffs Imposed Since 2018.” EconoFact, October 10, 2019. https://econofact.org/the-costs-of-u-s-tariffs-imposed-since-2018.

Steil, Benn, and Elisabeth Harding. “Steel Productivity Has Plummeted Since Trump’s 2018 Tariffs.” Council on Foreign Relations (blog), March 6, 2025. https://www.cfr.org/blog/steel-productivity-has-plummeted-trumps-2018-tariffs.

VanGrasstek, Craig. Skills and Techniques for Trade Negotiators: A Practical Guide. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), October 2022.

Williams, Aime, and Leo Lewis. “Donald Trump Threatens to Raise Tariffs Again on Japan.” Financial Times, July 1, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/0e65cca5-bf5b-4596-873e-e8c0502a9fda.