AI Has Been Adopted. So Why Is Productivity Still Hard to See?

by Mardoqueo Arteaga

Most large companies have formal policies, enterprise licenses, internal copilots, or approved tool stacks. In many sectors, AI is already embedded in day-to-day work. If adoption alone were the constraint, we should already see it in the productivity data.

And yet, the aggregate numbers remain underwhelming.

This tension is often framed as disappointment or hype fatigue. I think it is better understood as a timing and measurement problem. In this post, we will suggest a different, slightly more uncomfortable explanation to the fears of an AI bubble.

We are confusing purchasing software with economic adoption.

A Model of AI Adoption Dynamics

Before getting into the mechanics, it helps to be clear about what this section is trying to do. A model is not a forecast, and it is not a claim that all organizations behave like predictable spreadsheets. A "model" is a way to compress a messy situation into a few relationships that we can reason about consistently. If you keep the relationships in mind, the notation is intended as just a convenient shorthand.

I started with an observation: AI does not raise everyone’s productivity by the same amount. Workers who already have strong judgment, context, and domain knowledge tend to get more out of these tools than those who don’t.

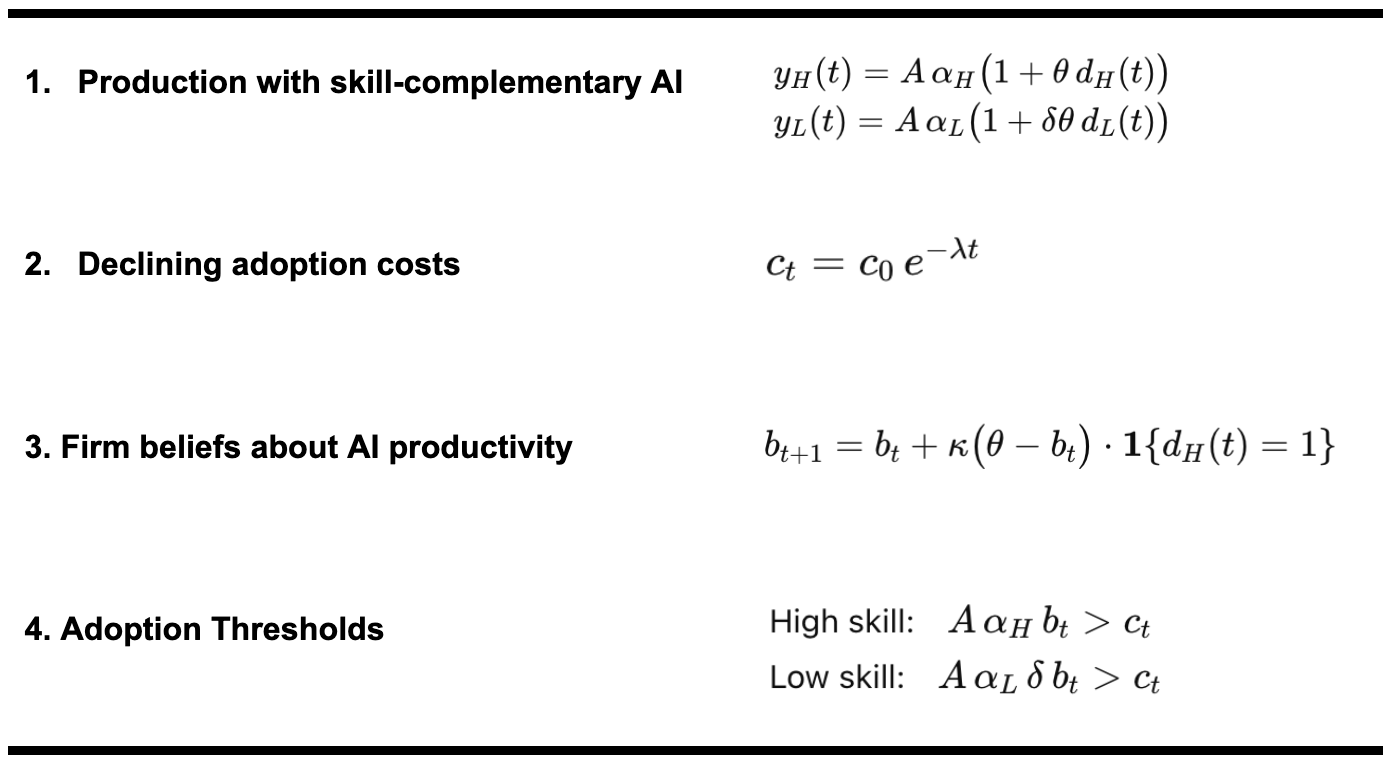

[1. Production]

One way to write that down is to let output depend on both baseline skill and whether a worker has access to an AI tool. For high-skill workers, output rises by a factor proportional to the AI’s true productivity boost. For lower-skill workers, the same tool helps too, but less so, reflecting a gap in how effectively the output can be translated into real work. This is Equation 1 in the figure below; don’t get too hung up on the notation but rather note that the same technology can be productive and unequal at the same time.

[2. Costs]

Adoption, of course, is not free. Even when AI tools are widely available, they come with costs: subscriptions, integration time, workflow redesign, and internal risk.

Those costs tend to fall over time as tools improve and competition increases. A convenient way to capture that is to let adoption costs decline gradually. This is captured in Equation 2, which posits the tension that a tool can be genuinely productive, yet still not worth formal adoption early on.

[3. Belief Friction]

The more subtle friction is informational. Workers learn how useful AI is the moment they start using it. Firms do not.

In the model, the firm holds a belief about how productive AI really is and updates that belief only after observing output. When no one is formally using the tool, that belief can remain stubbornly pessimistic, captured in Equation 3. In other words, learning happens only once someone is allowed to try. This is how skepticism can persist even when productivity gains are real.

[4. Adoption Logic]

Put the pieces in [1] - [3] together and the adoption rule becomes almost mechanical. A firm adopts AI for a group only when the expected productivity gain exceeds the cost.

For high-skill roles, that threshold is crossed earlier. For lower-skill roles, it takes longer, captured in Equation 4. The result is a staggered rollout that mirrors what many firms are experiencing in practice.

Original work product by Mardoqueo Arteaga.

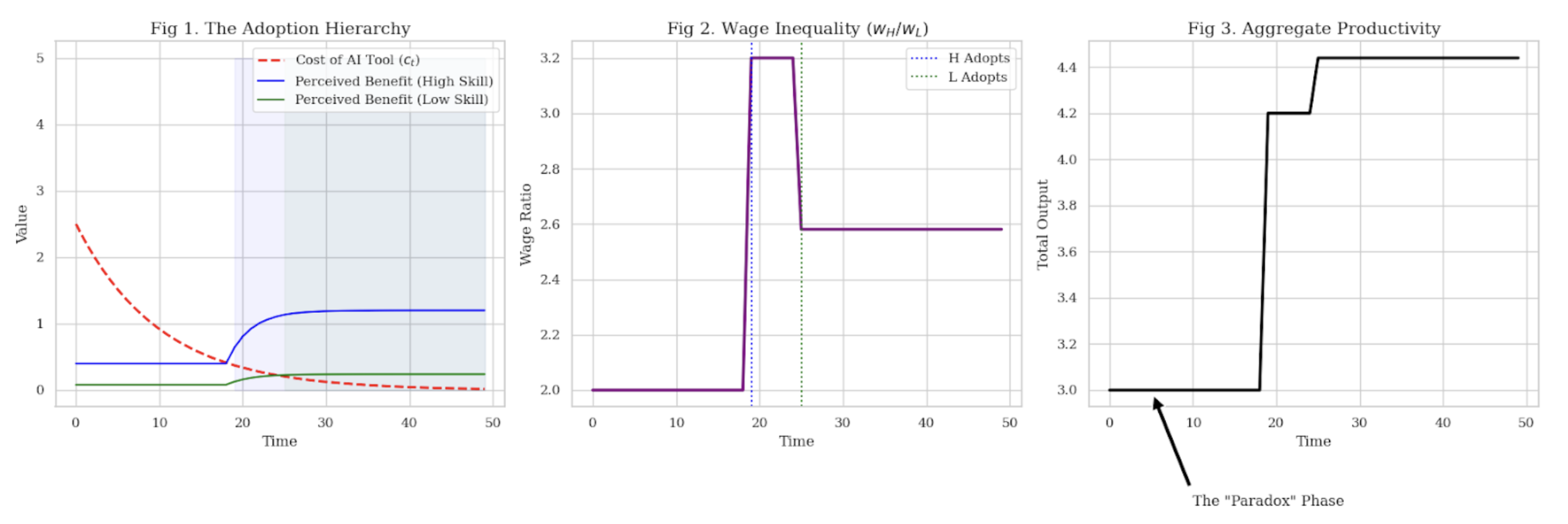

After doing some simulation, Figure 1 below shows what this looks like when you simulate the model:

High-skill adoption arrives first,

Wage inequality rises, and

Aggregate output barely moves.

Only later, when adoption spreads more broadly, does productivity show up in the data. Let’s unpack that a bit.

At the left of the figure is adoption pressure over time. Even when AI is formally available across an organization, the effective return from using it is not uniform. Tasks that require judgment, synthesis, and error correction tend to benefit earlier and more reliably than tasks that are tightly scripted or heavily supervised. This creates an adoption gradient, not in access, but in payoff.

That gradient matters because it shapes behavior. Workers and teams who see immediate gains change how they work quickly. Others wait. Over time, this creates uneven improvement even inside firms that have “already adopted AI.”

This disconnect shows up in a specific, painful way: inequality. The simulation predicts exactly what we are seeing in the labor market. When high-skill workers effectively adopt AI (whether formally or informally) their individual productivity spikes.

In a competitive market, this drives up their value relative to everyone else. The purple line in the middle chart shows this sharp rise in wage dispersion. It looks like a problem, but economically, it is a signal. It tells us the technology works, but only for those who already have the expertise to manage it. The "judgment gap" prevents low-skill workers from participating, keeping the benefits concentrated at the top.

That brings us to the right side of the figure. Aggregate productivity is a blunt object. It moves when enough tasks change, not when a subset becomes meaningfully more efficient. Early AI gains are real, but they are often concentrated, hard to measure, or absorbed as quality improvements rather than output increases. Firms also take time to reorganize around new tools, even after formal adoption.

Historically, this pattern is not unusual. General-purpose technologies tend to show up in micro data and case studies before they show up in macro statistics. The lag is not a failure of the technology. It reflects the time it takes to redesign work around it.

Takeaway

Seen this way, the current moment is less paradoxical than it appears. AI can be widely deployed, genuinely useful, and still invisible in headline productivity numbers for a while.

This framing does not imply that large productivity gains are guaranteed. It also does not imply that today’s skepticism is misguided. It simply suggests that adoption is not the same thing as absorption, and that diffusion within firms matters as much as diffusion across firms.

If productivity growth accelerates in the next few years, it will likely come from second-order changes: task redesign, training, and organizational learning, rather than from the initial rollout of tools themselves.

If it does not, that will tell us something important as well.

Either way, the question worth asking now is not “has AI been adopted,” but “where, how deeply, and with what complementary changes.” That is where the data will start to get interesting.

Sources:

Acemoglu, D. (2002). Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(1), 7-72.

Acemoglu, D. (2024). The Simple Macroeconomics of AI. NBER Working Paper No. 32487.

Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4B, pp. 1043–1171). Elsevier.

Agrawal, A., Gans, J., & Goldfarb, A. (2025). The Economics of Bicycles for the Mind. NBER Working Paper No. 34034.

Angeletos, G.-M., & Lian, C. (2022). Dampening general equilibrium: Incomplete information and bounded rationality. NBER Working Paper No. 29776.

Autor, D. (2015). Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3-30.

Bresnahan, T. F., & Trajtenberg, M. (1995). General purpose technologies ‘Engines of growth’?. Journal of Econometrics, 65(1), 83-108.

Brynjolfsson, E., Chandar, B., & Chen, R. (2025). Canaries in the coal mine? Six facts about the recent employment effects of artificial intelligence. Stanford Digital Economy Lab.

Brynjolfsson, E., Rock, D., & Syverson, C. (2021). The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1), 333-72.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (1998). The Origins of Technology-Skill Complementarity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 693-732.

Helpman, E. (Ed.). (1998). General purpose technologies and economic growth. MIT Press.

Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023). Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Science, 381(6654), 187-192.

Tomlinson, Kiran, et al. (2025) Working with AI: Measuring the Applicability of Generative AI to Occupations. arXiv, arXiv:2507.07935.