The Fed's Communication Channel is a Broken Functor

by Mardoqueo Arteaga

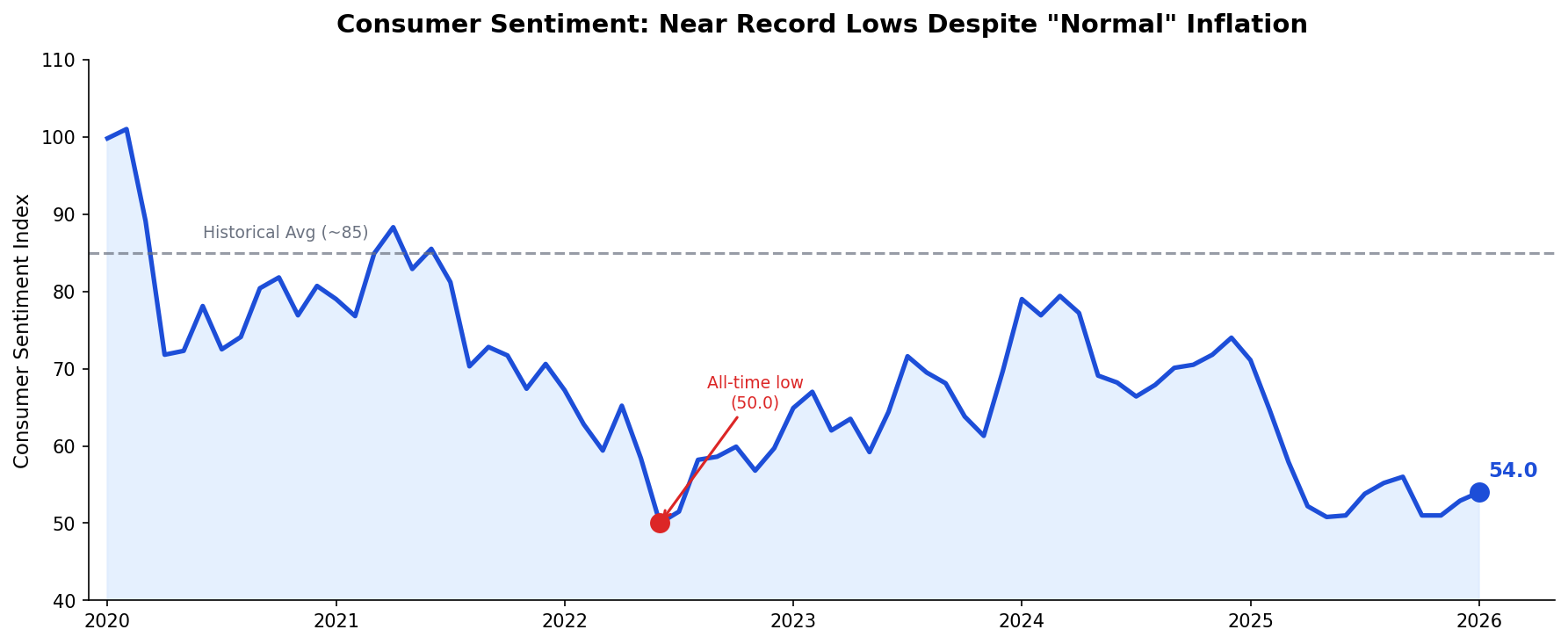

Consumer sentiment sits at 54, four points above the all-time low we hit in June 2022. Back then, inflation was 9.1%. Today it's 2.7%.

Something doesn't add up. And category theory, of all things, explains why.

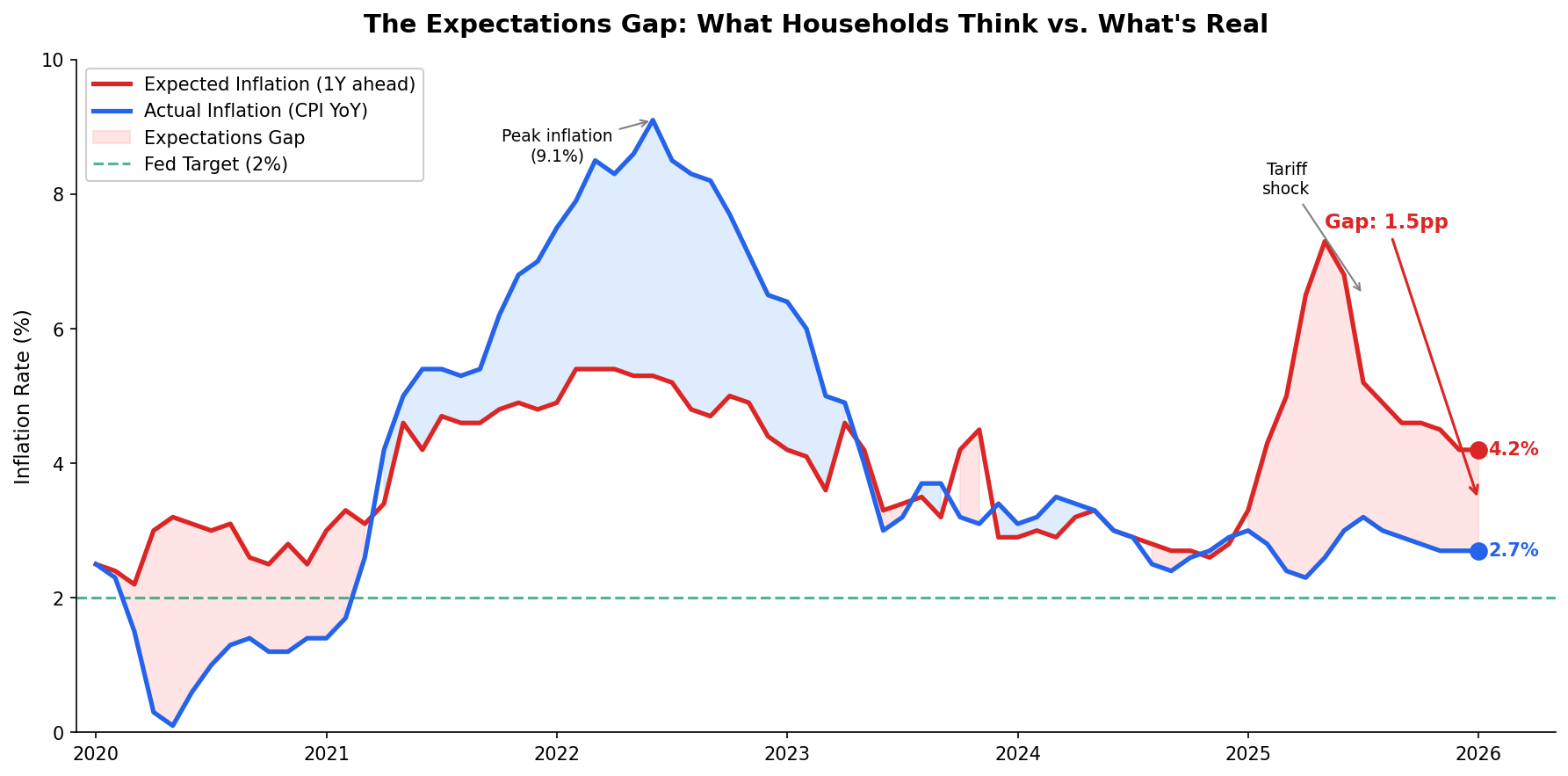

The Michigan survey came out last week. Households expect 4.2% inflation over the next year. Actual inflation is running at 2.7%. That's a 1.5 percentage point gap, and it's been persistent for months.

This gap is the whole ballgame. When people expect 4.2% and prices are rising 2.7%, they act as if inflation is still a crisis. They demand higher wages. They delay big purchases. They tell pollsters they feel terrible about the economy. The expectation becomes its own economic force. Once inflation becomes salient—once it's a "kitchen table issue," as Michigan's Joanne Hsu puts it—it takes years of countervailing evidence to dislodge.

I spent my PhD studying this exact problem: how households form expectations after Fed announcements. The short version is that the Fed's communication channel—the mechanism by which policy intentions translate into household beliefs—is structurally broken for most Americans. And there's a precise mathematical way to describe what "structurally broken" means.

A Quick Detour into Abstraction

Category theory is a branch of mathematics that cares less about what things are and more about how they relate. A category has objects (nodes) and morphisms (arrows between nodes). If you can go A → B and B → C, you can compose them into A → C.

A functor is a map from one category to another that preserves this composition. If f and g compose in the source category, their images F(f) and F(g) must compose the same way in the target:

F( g ∘ f ) = F( g ) ∘ F( f )

Break this rule and you don't have a functor. The structure doesn't transfer.

Now apply this to the Fed.

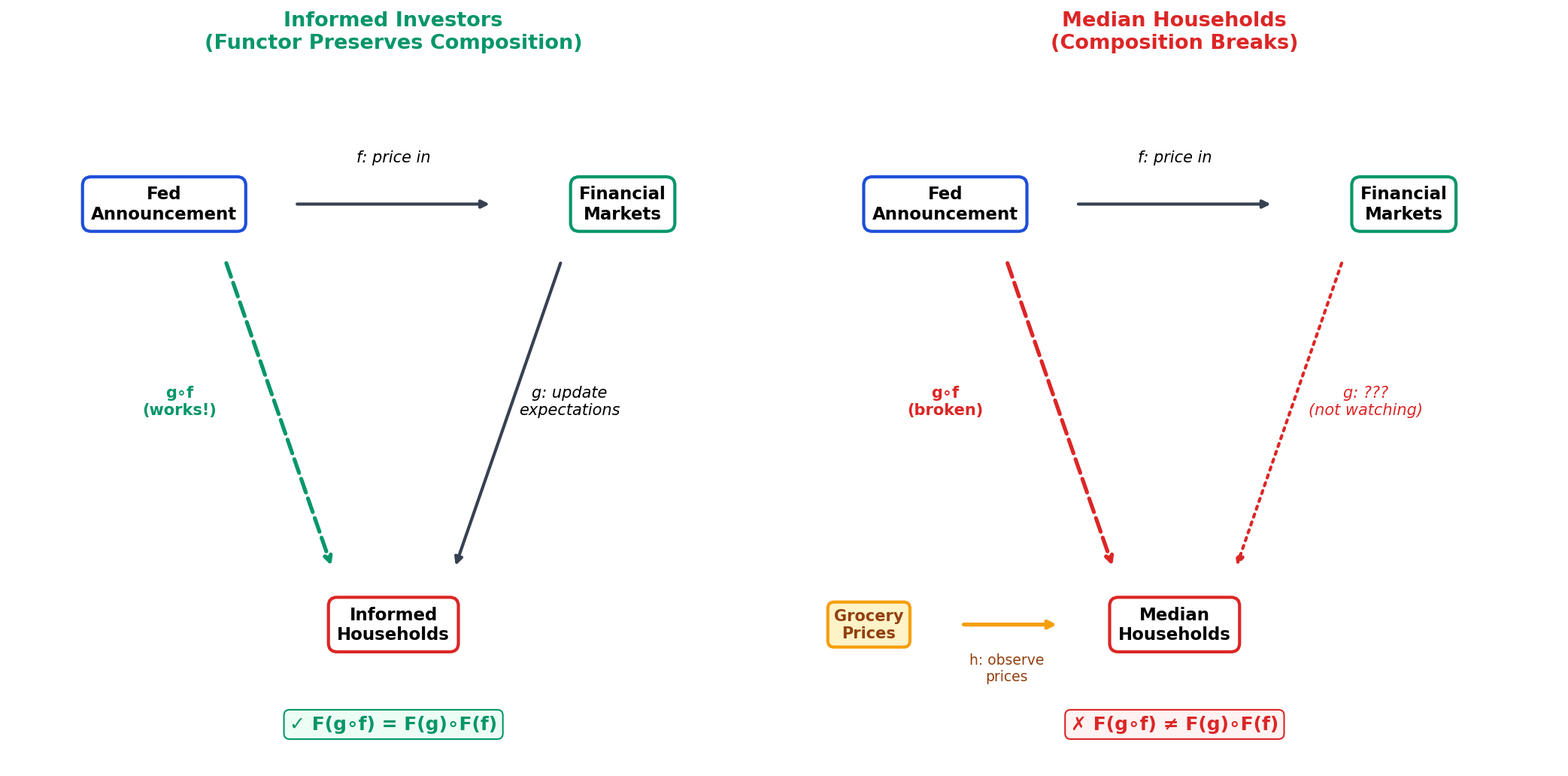

The intended communication channel looks like this:

Fed Announcement → Financial Markets → Household Expectations

The Fed releases a statement. Markets price it in immediately. Households observe markets (or hear about them) and update their beliefs. The composition Fed → Households should work by chaining through markets.

For informed investors, it does. My research found that Fed announcements shift expectations meaningfully among higher-income, higher-education respondents—people who follow financial news, have brokerage accounts, and pay attention to the dot plot.

For the median household, the composition breaks.

The Fed announces. Markets move. But median households aren't watching. They're watching grocery prices. The arrow from Markets → Median Households is dotted because it doesn't reliably transmit information. The morphisms exist individually, but they don't compose.

F( g ∘ f ) ≠ F( g ) ∘ F( f )

The functor property fails. The channel is broken.

The Michigan data below makes this concrete. (Sources here: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers, Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI, FRED.)

In January 2026:

Year-ahead inflation expectations: 4.2%

Actual CPI inflation: 2.7%

Consumer sentiment: 54 (vs. historical average of ~85)

Long-run inflation expectations: 3.4% (highest in months)

That last number is the warning sign. Long-run expectations are supposed to be anchored around 2-3%. When they drift to 3.4%, it suggests households aren't just reacting to current prices but rather that they're losing faith that inflation will stay low.

The New York Fed's research confirms the mechanism. During the pandemic, one-year-ahead expectations became highly responsive to inflation surprises, but three-year-ahead expectations became less responsive. Households are updating short-term beliefs aggressively based on what they see at the grocery store, while ignoring Fed signals about where inflation is headed.

This is exactly what a broken functor looks like. Information enters the system (Fed announces) but doesn't propagate through the intended chain (Markets → Households). Instead, a different arrow dominates: Grocery Prices(for example) → Household Expectations.

Why Does this Matter for 2026?

Powell's term expires in May. Trump will nominate a new chair (likely Kevin Hassett or Kevin Warsh), who will be seen as more willing to cut rates under political pressure.

Fed independence works as a commitment device. When households believe the central bank will hit 2% inflation no matter what (even if it means a recession) they adjust behavior accordingly. Wages moderate. Price-setting slows. The belief becomes self-fulfilling.

When households believe the Fed will cave, the commitment device weakens. Expectations drift. And the Fed needs to work harder to achieve the same result.

The risk isn't that the new chair cuts rates. The risk is that the transition itself damages credibility at exactly the moment when expectations are already unanchored.

Long-run expectations at 3.4% are the canary. If they keep drifting up, such as towards 4% or beyond, it means households are pricing in a Fed that won't (or can't) do what it takes. The functor will break further.

The standard policy response to unanchored expectations is aggressive communication: more press conferences, clearer forward guidance, louder commitment to the target. This works when the channel is intact—when Fed → Markets → Households composes correctly.

But if the channel is broken, louder signals don't help. You're yelling into a void.

The alternative is to fix the composition. Either:

Rebuild the Markets → Households arrow: Find ways to make Fed signals reach median households directly. This is hard. Financial literacy campaigns have limited evidence of success.

Bypass markets entirely: Communicate through channels households actually use. Grocery prices, gas prices, rent. This is what the "inflation is transitory" messaging tried (and failed) to do.

Accept the broken functor: Recognize that household expectations will lag reality by 12-18 months, and plan policy around that lag. This is probably where we are.

None of these are satisfying. But the first step is diagnosing the problem correctly. The Fed's challenge isn't that households disagree with policy. It's that the communication structure doesn't preserve composition for most Americans.

Conclusion

I don’t think monetary policy is what the mathematicians who invented category theory in 1945 were concerned about. But the abstraction they built (objects, morphisms, composition) turns out to describe information channels precisely. A channel that works is a functor: structure in, structure out. A channel that fails isn't.

The Fed is operating a broken functor. Until that changes, the gap between expectations and reality will persist. And consumer sentiment will stay near record lows even when the inflation battle is, by the numbers, mostly won.

Works Cited:

Arteaga, M. Monetary Policy Announcements and Household Expectations of the Future. Journal of Economic Analysis, 2026, 5, 130. https://www.anserpress.org/journal/jea/5/1/130

Armantier, Olivier, et al. "How Have Households' Inflation Expectations Responded to Inflation?" Liberty Street Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2022. https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/tag/inflation-expectations-michigan-survey/

Hsu, Joanne. "Surveys of Consumers: Preliminary Results for January 2026." University of Michigan, January 2026. https://www.sca.isr.umich.edu/

iShares. "Fed Outlook 2026: Rate Forecasts and Fixed Income Strategies." BlackRock, January 2026. https://www.ishares.com/us/insights/fed-outlook-2026-interest-rate-forecast

Morningstar. "What's Next for the Fed in 2026?" January 2026. https://www.morningstar.com/markets/whats-next-fed-2026

Piger, Jeremy, and Daniel Chapman. "What Survey Measures of Inflation Expectations Tell Us." Economic Brief, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, January 2023. https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2023/eb_23-03

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL]." Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL

University of Michigan. "University of Michigan: Inflation Expectation [MICH]." Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MICH

University of Michigan. "University of Michigan: Consumer Sentiment [UMCSENT]." Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UMCSENT

Zandi, Mark. "Economic Outlook 2026." Moody's Analytics, December 2025.