Monetary Policy for People Who Were Not Listening

by Mardoqueo Arteaga

Central bankers like to say that monetary policy works through expectations. A beautiful concept implying a public that is constantly calculating, analyzing, and adjusting to the Fed's subtle signals. But that sophisticated engine only runs, of course, if someone actually bothers to update those expectations. In a paper I have forthcoming in the Journal of Economic Analysis, I dig into this very question: Do U.S. households truly revise their core assumptions about inflation, interest rates, and housing when the Federal Reserve makes an announcement? The period I examined (2013 to 2021) was nearly a decade full of unconventional tools, "forward guidance," and agonizingly slow normalization. This was the perfect test bed to see how much of the Fed's careful communication truly reaches the public.

The short answer? It reaches them, but on very narrow terms.

Households hear rate decisions. They absorb clear signals. They certainly notice when the Fed does nothing at all. What they do not do, it turns out, is fully process a complex, multi-instrument announcement. They don't rewrite their three-year economic outlook based on a single paragraph of guidance (if they even think about this time horizon). In other words, the communication channel is indeed open; the troubling news is that it remains profoundly narrow.

This finding is especially relevant for our world in 2025. Central bank independence is now being vigorously debated on the public stage. If the households didn't hear the Fed when policy was calm(er), it will be exponentially harder to convince them when policy becomes noisy.

How the Information Channel Works (and breaks)

The classic textbook transmission was a simple, straight-line shot: The Fed signals, households adjust, the economy obeys. But in practice, the signal doesn't travel in a straight line; it takes a detour through a maze of distortions. (Don’t we all?)

Between the press conference podium and your dinner table, policy language gets filtered, often violently, through partisan headlines, self-appointed “influencers,” and political talking points. By the time someone hears that “the Fed cut rates,” (like they did last week) the meaning has already been re-written: for some, it suggests cheaper mortgages; for others, it’s a terrifying sign that inflation is returning. The message begins as technical economics, yes, but by the time it lands, the interpretation is almost entirely social and personal.

That kind of distortion is nothing new, but its velocity certainly is. Algorithms, hyper-specialized media, and a flood of analysts (some brilliant, many terrible, yours truly being somewhere in between) amplify the noise faster than the Fed can possibly clarify its intent. In pure information terms, the transmission mechanism now has more bandwidth, yet dramatically less signal.

From Background Noise to Personal Pain

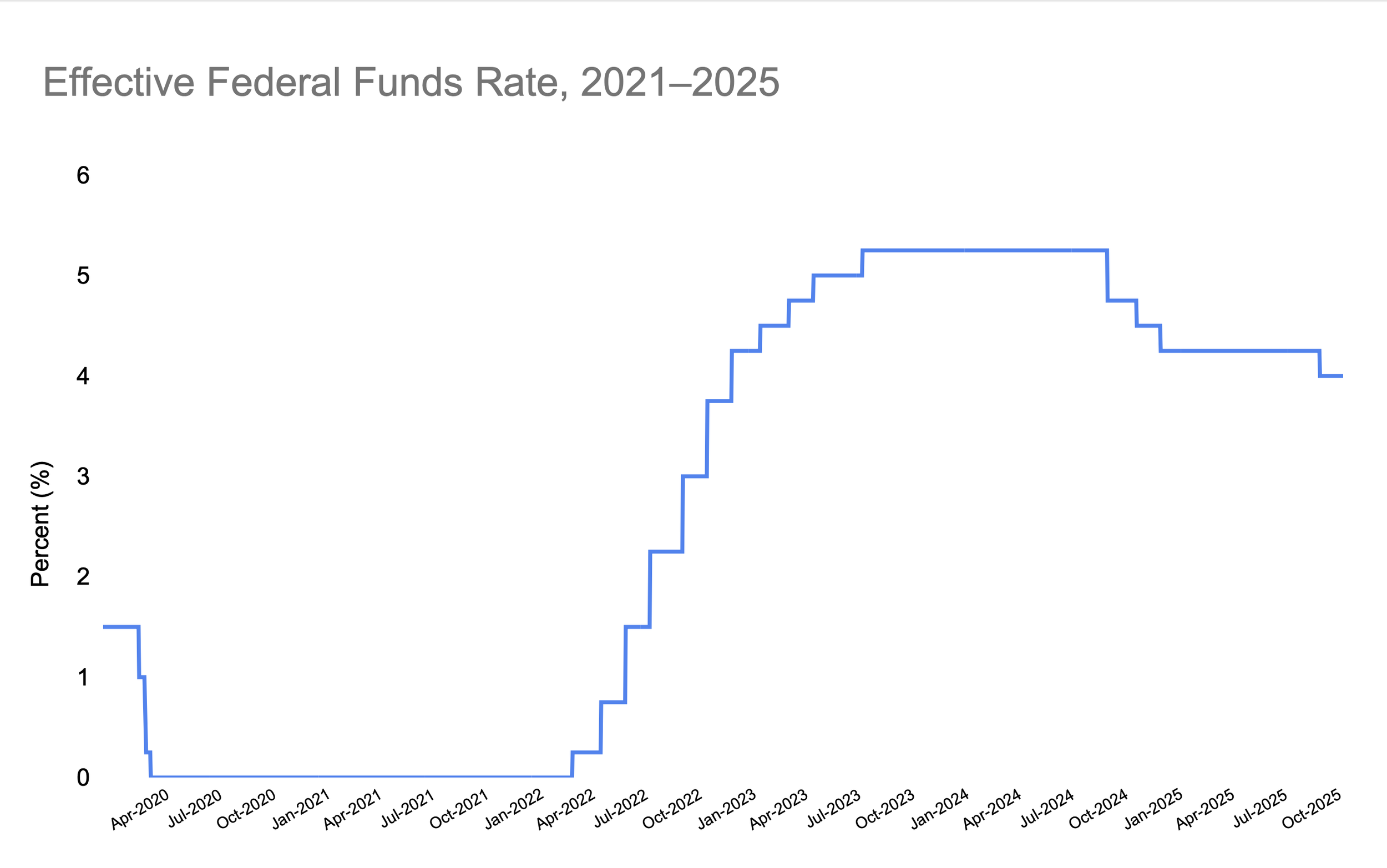

The past three years transformed the Fed from background noise no one paid attention to into an inescapable roar. After keeping rates near zero for years, policymakers hiked them at the fastest clip in a generation.

The chart below tells the story more clearly than any policy speech:

Source: Federal Reserve

Every step in that relentless line represented a new headline, a new explanation, and a completely new expectation. Households that once ignored FOMC meetings started watching rate decisions like weather forecasts. The pain of inflation, the sudden payoff of savings accounts, and the paralyzing squeeze of higher credit costs made monetary policy personal, a new paradigm that, while something that had occurred in the past, is occurring during a whole new context in society.

Recent surveys confirm this shift. A 2025 global survey by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) finds that households are tracking central bank actions more closely than at any time in recent memory, yet their understanding of policy remains uneven. People are aware of rate changes, but they interpret them through the lens of personal experience: inflation, mortgage costs, and job security.

Academic literature on the subject has also blossomed: Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2025) show that inflation expectations among households have become more reactive to news but remain poorly anchored, oscillating with the flow of media narratives rather than fundamentals. New working papers by Jeong et al (2025) and Pfajfar & Winkler (2025) strengthen this point: attention itself has become a policy variable. Jeong et al demonstrates that households with greater financial exposure (such as homeowners and equity investors) are significantly more responsive to monetary news, while Pfajfar & Winkler show that households have formed explicit, and often divergent, preferences about inflation and interest rates. Together, these findings reveal an economy in which the line between information and emotion has blurred. Households are no longer indifferent to the Fed’s language, and they are decoding it, sometimes incorrectly, but with unprecedented intensity.

In short: Attention has improved. Precision has not.

The Real Puzzle: Attention is the Currency

For an information economist, this is the true paradox. The bottleneck holding the economy back isn't cash flow or credit. It's the simple, finite currency of human attention.

The Fed can publish every “dot plot” in high definition. It can simplify its statements, launch explanatory videos, or even experiment with AI-generated summaries. None of that ensures comprehension, because comprehension competes fiercely with everything else that demands a headline. In an economy where attention is the primary currency, the Fed is easily registered as another content producer.

This creates a self-defeating cycle: The more the Fed explains, the more narratives it invites. A rate cut meant purely to stabilize markets can easily become a political story about weakness; a pause can instantly become a story about fear. The policy itself is technical. The interpretation is almost always emotional.

If you're wondering what to do with all this noise, I recommend starting here: Treat information like policy itself, meaning in aggregates and not anecdotes.

The Fed rarely surprises markets twice in a row. What matters for the honest economist is the direction and persistence of the signal, not the ephemeral noise around a single meeting. When you hear that rates have fallen by a quarter-point, the right question isn't “What will happen tomorrow?” but “What does this quarter-point movement say about the path ahead?”

Pay attention to clarity. The moments when the Fed speaks most plainly tend to be when expectations stabilize and the economy breathes a sigh of relief. Complexity always breeds confusion. As my and other research shows, households respond best to simple, clear policy messages. That lesson holds true for us economists, too.

The great experiment of the past decade has been to see whether communication can truly substitute for action. It can, but only when the people are actually listening.

In 2025, households finally are. The clear danger is that policymakers will mistake that newfound attention for genuine understanding. The challenge ahead, then, isn't to make policy louder. It’s to make it truly legible.

Works Cited:

Francesco D'Acunto & Fiorella De Fiore & Damiano Sandri & Michael Weber, 2025. “A global survey of household perceptions and expectations,” BIS Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, September.

Olivier Coibion & Yuriy Gorodnichenko, 2025. “Inflation, Expectations and Monetary Policy: What Have We Learned and to What End?,” NBER Working Papers 33858, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Jeong, Jaemin, Eunseong Ma, and Choongryul Yang (2025). “Attention-Dependent Monetary Transmission to Household Beliefs,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2025-084. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2025.084.

Damjan Pfajfar & Fabian Winkler (2024). "Households' Preferences Over Inflation and Monetary Policy Tradeoffs," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2024-036, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Arteaga, Mardoqueo, 2025. “Monetary Policy and Household Expectations of the Future,” Forthcoming in the Journal of Economic Analysis.

Federal Reserve Board. “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 29 Oct. 2025, www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20251029a.htm