Stop Doomscrolling, and Start Stress-Testing: How Geopolitics Hits the Economy and Your Wallet

by Kent O. Bhupathi

On Saturday, my phone didn’t just buzz… it practically tried to achieve orbit!

I had actually managed to fall asleep like a responsible adult who swears they’re “cutting back on news,” and then woke up to an avalanche of alerts about a major geopolitical rupture in Venezuela. You know, the kind of headlines that makes you blink twice and think, “oh, geeze… not again! Not another one!” Somewhere in my brain, the Chris Farley meme was already putting on its awful, brown tie and reporting for duty: “Getting pretty tired of living through historical events.”

That joke may be doing an irresponsible amount of emotional labor right now. And for that, I apologize.

But the thing about “historical events” is that they do not stay politely overseas. They show up at the gas pump. They show up in shipping costs. They show up in corporate earnings calls, Fed statements, the formerly humble act of trying to buy groceries without quietly spiraling, and so much more.

Within literal minutes, the second wave hit: texts, emails, and “quick calls.” Colleagues. Clients. Friends. Family.

“Does this mean inflation again?”

“What happens to oil and electricity?”

“Should we freeze hiring?”

“Is my 401(k) about to take a hit?”

“If I’m not in the war zone, should I even care?”

These are all fair, albeit exhausting, questions, because they ask for certainty in a world that is structurally allergic to it.

So, let’s make a deal… I won’t pretend every geopolitical tremor is a five-alarm financial fire. And you won’t pretend these things are “just politics” with no economic consequences.

Here’s the good news: you don’t need certainty to make good decisions. What you need a transmission map.

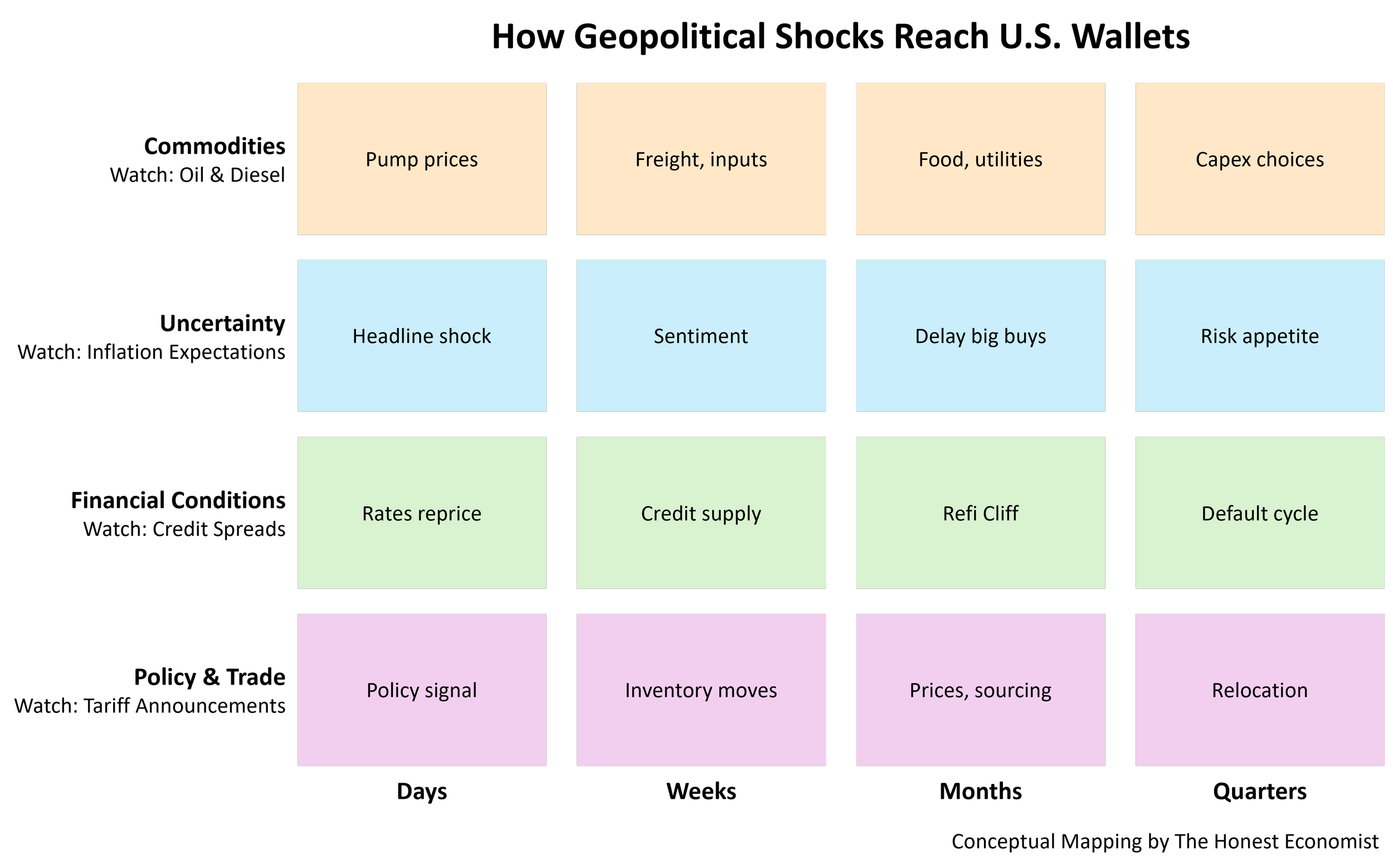

In practice, geopolitical shocks reach U.S. households and businesses through four channels:

Commodities;

Uncertainty;

Financial Conditions; and

Policy/Trade.

The research is blunt about the stakes. Wars are obviously economically devastating for the countries involved: one study covering 115 conflicts over 75 years finds war reduces real GDP by about 13%, with about an 11% drop in consumption and 14% collapse in investment, plus worsening public finances and big inflation effects when governments finance conflict through money creation (pushing the price level up by nearly 50% over a conflict’s duration).

But you don’t have to be in the blast radius to feel the shockwave. You just need to buy gas, pay-off your credit-card(s), run a hiring plan, or manage a budget.

The Headline-to-Wallet Pipeline

If you only remember one thing, make it this: your real question isn’t “Is this bad?” It’s “Which channel is activated, and how fast?”

Channel 1: Commodities (fast). Conflicts that touch oil, food, or shipping lanes reprice essentials quickly. Commodity price effects are often immediate in markets and filter into household bills within weeks.

Channel 2: Uncertainty (quiet but powerful). Even the threat of conflict can make firms delay hiring and investment. Spikes in measured geopolitical risk predict weaker investment and employment.

Channel 3: Financial conditions (medium). Risk-off moves and later rate hikes change borrowing costs and job conditions with a lag.

Channel 4: Policy and trade (usually a slow fuse). Trade deals and trade wars reshape prices and job structures over years, often with small national averages and big local impacts.

Commodities: the Fast Channel that Bullies Everyone’s Budget

When a conflict threatens supply of oil, gas, grain, or fertilizer, the first thing to move is price, and the second thing to move is your mood.

The Ukraine invasion is a clean example of the mechanism. Researchers estimate it lifted global inflation by roughly 1–2.5 percentage points and lowered world GDP by 0.7–1.5% within a year. In the U.S., gasoline prices jumped about 45 cents in a week after the invasion (the fastest rise since 2005).

There’s a practical rule of thumb that helps translate “oil spike” into “macro problem”: every $10 per barrel increase in oil tends to add about 0.2 percentage points to U.S. inflation and cut GDP growth by about 0.1 points. For the record, that’s not a prophecy. It’s but a reminder that energy is a foundational input. And when it gets pricier, it squeezes everything from shipping to heating to the cost structure of a lot of businesses.

For households, these spikes act like an inflation tax. People feel it first at the pump and in food bills, where it hits lower-income households harder because essentials consume more of their budget.

What to watch after the headline: commodity futures, gasoline and diesel prices, food and fertilizer prices, and whether the inflation spike shows up in CPI quickly. History suggests war-driven inflation often appears in official inflation prints within one or two reporting periods.

Uncertainty: the Hiring Freeze You Don’t See Coming

The second channel is less dramatic than a price chart, but it’s how geopolitics sneaks into the labor market.

A widely used geopolitical risk index shows spikes in risk foreshadow lower investment and employment, and even raise the probability of severe downturns. Put plainly, when the future gets foggy, businesses get cautious.

Essentially, this matters because most professional pain during geopolitical turbulence comes from delayed decisions. Capital spending gets postponed. Hiring pipelines slow. Procurement teams hedge. Clients become “value conscious” in that special corporate way that means “we are now allergic to signing,” and the procurement teams laugh their way to the bank…

And you don’t need a full-scale war for this to bite. The research notes that saber-rattling and military drills around critical supply chain chokepoints can unsettle planning (think semiconductors) and make firms in exposed industries cut capital spending.

What to watch after the headline: capex guidance, PMI new orders, corporate hiring plans, and credit conditions for smaller firms. Uncertainty usually hits investment first, then labor.

Financial Conditions: Where Volatility Turns into Real Life

Markets react instantly. Households feel it later, but sometimes harder.

During geopolitical crises, stocks often drop on uncertainty and risk aversion; investors flee to safe assets like Treasuries, gold/silver, and dollars. If you’ve got a 401(k), you’ll see the mark-to-market drama early. But the bigger household effects often arrive through interest rates and job conditions.

Here’s the sequence the research lays out: Treasury yields can fall at first on a flight to safety, which can briefly ease mortgage rates. But if conflict contributes to persistent inflation, yields rise later as central banks tighten. That tightening flows into higher borrowing costs on mortgages, car loans, and credit cards, which becomes a delayed but meaningful hit to household cash flow.

Meanwhile, oil shocks have a grim habit of showing up before recessions; historical examples include the 1973 Middle East war and oil embargo, 1979 Iran crisis, and 1990 Gulf War contributing to U.S. downturns.

A translation for decision-makers: sometimes the “financial market event” is the preview, not the movie. The movie is what happens when higher rates meet fragile budgets and cautious hiring.

Policy and Trade: Slow Fuse and Uneven Pain

Trade policy is where people get whiplash because both of these can be true. Trade liberalization can raise overall efficiency and lower prices. And the adjustment costs can be geographically concentrated and persistent.

NAFTA is the canonical example of “small average, big local.” One structural study found NAFTA increased overall U.S. welfare by roughly 0.1%, while Mexico saw a bigger gain (about 1.3%). That is not nothing, but it’s also not the kind of national surge that makes headlines.

Now zoom in. Research on local labor markets finds the aggregate effect can look modest while certain regions and blue-collar workers in highly exposed industries experience dramatically weaker wage growth.

And then there’s the “China shock,” which is basically a decade-long lesson in slow-motion disruption. A summary of the literature notes that by 2011, China’s WTO entry is associated with about 2.4 million U.S. jobs lost in exposed regions, with depressed earnings and limited recovery even a decade later.

On the flip side, protectionism can hit quickly through prices. Tariffs function like a regressive tax on consumers: basic imported goods cost more, and domestic producers may raise prices too when foreign competition is handicapped. Some research estimates that recent tariff increases cost the average household on the order of $1,200–$1,700 per year in higher prices.

So when you hear about a major trade deal, or a new tariff round, the correct question is not “Is trade good or bad?” It’s: who is exposed, where, and for how long?

What Policymakers Should Do

1) Avoid inflationary financing and protect central bank credibility

When shocks hit and emergency spending becomes unavoidable, the temptation is to “figure it out later.” History suggests that’s how temporary shocks become persistent inflation. Wars often worsen fiscal balances and are frequently financed through borrowing and money creation, with wartime inflation a common outcome.

Action: pair emergency spending with transparent medium-term fiscal plans and debt-management choices that reduce rollover risk, and communicate the inflation objective clearly so second-round effects don’t take hold.

2) Budget the lifetime costs, not just the “operations” costs

War costs don’t stop when the headlines do. Don’t you wish they did‽ Beyond direct expenditures, long-horizon obligations (e.g., veterans’ care, disability, interest) can run into the trillions. With respect to Iraq and Afghanistan, some estimates put the debt impact at $2–3 trillion once veterans’ care and interest are counted.

Action: require conflict-related fiscal packages to include an annex of long-horizon obligations with sensitivity ranges.

3) Pair trade agreements with adjustment policy that matches geography and persistence

The research is consistent: trade shocks can be locally concentrated and slow to unwind, even when national aggregates are small.

Action: pre-fund place-based adjustment supports (mobility help, wage insurance pilots, demand-driven retraining) for vulnerable regions.

Sure… all easier said than done in politics. But, we are at a point of crisis when concerning the fundamentals. Perhaps the most basic just needs to be said!

What Households Should Do

If policymakers get a steering wheel, households get a seatbelt. It’s not fair, but it’s life.

1) Build liquidity buffers and formalize an “emergency cashflow plan”

Your biggest enemy during geopolitical inflation isn’t “bad markets.” It’s being forced into bad decisions because the timing is awful. Conflicts can squeeze budgets fast through fuel and food prices.

Action: keep a defined liquid buffer for essentials, and pre-commit your hierarchy (cut discretionary, negotiate bills, draw emergency fund, only then touch high-cost credit).

2) Reduce exposure to payment shocks from variable-rate debt

When inflation spikes and central banks tighten, borrowing costs rise with a lag, and that’s when budgets crack.

Action: identify variable-rate exposure, stress-test rate resets, and prioritize refinancing or faster principal reduction where feasible.

3) Align risk assets to your time horizon so you avoid forced selling

Geopolitical risk increases market volatility and can tighten financial conditions.

Action: keep near-term obligations funded with lower-volatility, liquid instruments so you’re not selling long-term investments at the worst moment.

Don’t Outsource Your Financial Plan to Breaking News

The meme is funny because it’s true. We are living through a lot!

But the point of a framework isn’t to predict the next headline, but rather to stop treating every headline like a personal financial emergency. Most geopolitical stories do not hit everyone equally, and they don’t hit everything at once. Prices can move in days. Hiring and investment can shift over months. Debt and policy bills can arrive years later.

You can’t control geopolitics. You can, however, control fragility. And that is the difference between being informed and being financially whiplashed.

Sources:

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David Weinstein. “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare.” NBER Working Paper 25672, National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2019. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25672.

Associated Press. “Tariffs Have Cost US Households $1,200 Each Since Trump Returned to the White House, Democrats Say.” 1011NOW, December 11, 2025. https://www.1011now.com/2025/12/11/tariffs-have-cost-us-households-1200-each-since-trump-returned-white-house-democrats-say/.

Auer, Cornelia, Francesco Bosello, Giacomo Bressan, Elisa Delpiazzo, Irene Monasterolo, Christian Otto, Ramiro Parrado, and Christopher P. O. Reyer. “Cascading Socio-Economic and Financial Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine War Differ Across Sectors and Regions.” Communications Earth & Environment 6 (2025): Article 194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02119-1.

Auray, Stéphane, Michael B. Devereux, and Aurélien Eyquem. “Tariffs and Retaliation: A Brief Macroeconomic Analysis.” NBER Working Paper 33739, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2025. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33739.

Baffes, John, and Peter Nagle. “How to Mitigate the Impact of the War in Ukraine on Commodity Markets.” Brookings (Brookings Institution), July 1, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-to-mitigate-the-impact-of-the-war-in-ukraine-on-commodity-markets/.

Benmelech, Efraim, and Joao Monteiro. “The Economic Consequences of War.” NBER Working Paper 34389, National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2025. https://doi.org/10.3386/w34389.

Bloom, Nicholas. “The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks.” Econometrica 77, no. 3 (May 2009): 623–685. https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~dbackus/GE_asset_pricing/Bloom%20uncer%20shocks%20Ec%2009.pdf.

Caldara, Dario, and Matteo Iacoviello. “Measuring Geopolitical Risk.” American Economic Review 112, no. 4 (April 2022): 1194–1225. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20191823.

Caliendo, Lorenzo, and Fernando Parro. “Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA.” NBER Working Paper No. 18508, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2012. https://www.nber.org/papers/w18508.

Clausing, Kimberly, and Mary E. Lovely. “Trump’s Tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China Would Cost the Typical US Household Over $1,200 a Year.” Peterson Institute for International Economics, February 3, 2025. https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2025/trumps-tariffs-canada-mexico-and-china-would-cost-typical-us-household.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “Adjustable-Rate Mortgages: Find Out How Your Payment Can Change Over Time.” ConsumerFinance.gov, October 13, 2022. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/owning-a-home/explore/adjustable-rate-mortgages/.

Costs of War Project. “Economic | Costs of War.” Costs of War, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University. https://costsofwar.watson.brown.edu/costs/economic.

Daggett, Stephen. Costs of Major U.S. Wars. Congressional Research Service Report RS22926, Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, July 24, 2008. https://www.congressionalresearch.com/RS22926/document.php.

Dizikes, Peter. “Q&A: David Autor on the Long Afterlife of the ‘China Shock’.” MIT News, December 6, 2021. https://news.mit.edu/2021/david-autor-china-shock-persists-1206.

Dunsmuir, Lindsay. “No Inflation Relief in Sight for U.S. as Impact of Ukraine War Intensifies.” Reuters, March 7, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/us-inflation-set-heat-up-further-impact-ukraine-war-intensifies-2022-03-07/.

Hakobyan, Shushanik, and John McLaren. “Looking for Local Labor Market Effects of NAFTA.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 98, no. 4 (October 1, 2016): 728–741. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00627.

Hanedar, Emine, Gee Hee Hong, and Celine Thevenot. “Fiscal Policy for Mitigating the Social Impact of High Energy and Food Prices.” IMF Notes 2022, no. 001 (June 7, 2022). https://www.imf.org/en/publications/imf-notes/issues/2022/06/07/fiscal-policy-for-mitigating-the-social-impact-of-high-energy-and-food-prices-519013.

McLaren, John, and Shushanik Hakobyan. “Looking for Local Labor Market Effects of NAFTA.” NBER Working Paper 16535, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2010, revised January 2012. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16535

Ural Marchand, Beyza. “How Does International Trade Affect Household Welfare?” IZA World of Labor 378 (August 2017). https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/378/pdfs/how-does-international-trade-affect-household-welfare.pdf.

Wolla, Scott A. “When the Unexpected Happens, Be Ready with an Emergency Fund.” Page One Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, September 2, 2025. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/page-one-economics/2025/sep/when-unexpected-happens-be-ready-with-emergency-fund.