Why I'm Betting on Bodies, Not Just Brains

by Mardoqueo Arteaga

If you have been reading this blog for a bit now, you know we have been skeptical of the “AI Bubble.” Our skepticism, or at least my own, has mostly centered around the economic implementation lagging the hype. We spent the better part of 2025 watching companies buy massive amounts of GPU compute to build smarter chatbots, yet aggregate productivity statistics barely budged. (Yes, we have *some* data now that shows the effects of AI on productivity, but not nearly as much as you would think).

While the market was distracted by the “Brain” trade (LLMs, data centers, and NVIDIA chips), you may have missed the momentum building in the “Body” trade.

We are entering 2026 with a massive valuation gap between the AI that thinks and the AI that moves. For the Honest Economist, that gap looks less like a discrepancy and more like an opportunity.

The Tale of Two Indices

Since the debut of ChatGPT in late 2022, the market has bifurcated in a way that tells a fascinating story about investor psychology. The Bloomberg AI Aggregate Index (BAIAT:IND), which is composed of, or dominated, by software, cloud, and chip makers, has nearly tripled. Even after recent pullbacks, it trades at roughly 31 times earnings and 6 times sales. The market is betting heavily that the future of value creation is digital.

In contrast, the Bloomberg Robotics Aggregate Index (BROAT:IND), which are the companies building industrial automation, actuators, and machinery, is up only 50%. It trades at a much more modest 24 times earnings and roughly 2.6 times sales.

Investors are implicitly betting that physical labor is either too hard to automate or simply not worth the capital expenditure compared to software. I believe this bet is wrong, at least in the mid-term.

The Demographic Reality Check

This valuation gap is colliding with a demographic storm that is no longer too distant. I’ve made no effort to hide McKinsey’s demographic report from earlier this year in other posts, but some sobering statistics on the changing tides should be sufficient: Japan saw just 720,000 babies born in 2024, the lowest number in over a century, while deaths far outnumber births. South Korea holds the world’s lowest fertility rate at roughly 0.7 children per woman. Even in Europe, the working-age population is projected to shrink by 20% by 2050.

In Japan’s nursing care sector, there is currently only one applicant for every 4.25 job openings. We are simply running out of humans to do the work.

Scarcity is already forcing adoption. South Korea now has the world's highest robot density at over 1,000 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers. Amazon has deployed over 750,000 mobile robots to move goods, saving billions annually. Agility Robotics has opened a factory in Oregon capable of producing 10,000 humanoid robots per year. The demand for “embodied labor” is real, and it is growing faster than the market's pricing suggests.

The Death of Moravec's Paradox

For decades, robotics failed to scale because of Moravec's Paradox. It was easy to make a computer beat a Grandmaster at chess, but incredibly hard to make it fold a laundry basket. This kept robots confined to cages in automotive factories, doing repetitive, pre-programmed welds.

Two catalysts broke this paradox in 2025.

The first is simulation. We are no longer training robots in the real world, which is slow and expensive. We are training them in physics-compliant simulations, like NVIDIA's Isaac Sim. Citrini Research calls this the “Matrix Dojo.” We can run 10,000 years of “folding laundry” training in a single night of GPU time, driving the marginal cost of acquiring physical experience to near zero.

The second is hardware deflation. The cost of actuators and sensors is collapsing, driven largely by manufacturing scale in China. We are seeing unit costs for humanoid robots fall significantly, making the economics of deployment finally make sense.

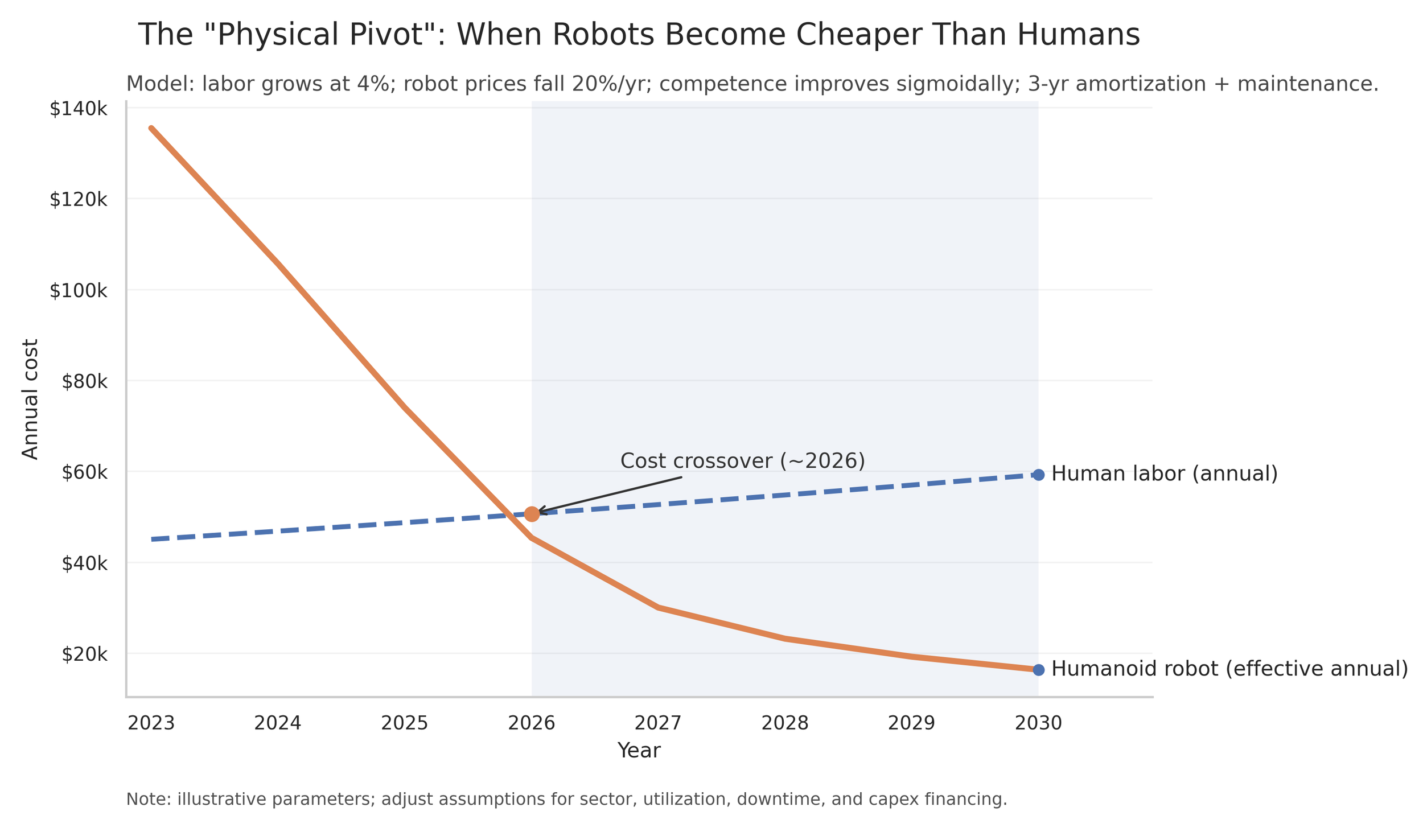

Visualizing the Economic Crossing Point

To understand why this matters for 2026, I built a simple simulation to model the Economic Crossing Point. This is the moment when the effective cost of a humanoid robot (factoring in competence and price drops) falls below the cost of human labor in an aging economy.

The code below models three variables: the declining cost of robots via Wright's Law, the rising cost of labor due to demographic scarcity, and the rising competence of robots via simulation.

On one side, we have the Blue Line: the cost of human labor, which is structurally rising due to demographic scarcity (fewer workers means higher wages). On the other, we have the Orange Line: the ‘effective cost’ of a humanoid robot.

Note that I use effective cost. In 2023, robots were expensive and barely worked (low competence), making their effective cost astronomical. But thanks to simulation-based training, competence is rising sigmoidally just as hardware costs plummet. The result is a deflationary collapse in the red line. The moment these lines cross in 2026 (the orange dot) is the 'Physical Pivot.' That is the moment when a robot shifts from being an R&D science project to a deflationary asset class that every CFO will need to hedge against labor inflation.

The Monetary Tailwind

As the chart suggests, we are likely hitting the crossover point this coming year. This creates a massive macroeconomic tailwind. Jensen Huang estimates this opportunity at $50 trillion because robots are deflationary capital. In a world where birth rates are collapsing, the only way to keep GDP growing without rampant inflation is to substitute labor with capital.

There is also a monetary policy angle that few are discussing. For the last two years, high interest rates have punished capital-intensive industries like robotics and rewarded asset-light software. But with the Federal Reserve cutting rates multiple times in 2025 and potentially more in 2026, the cost of financing physical fleets will drop.

The “Body Trade” is essentially a call option on lower real rates. As financing becomes cheaper, CFOs will find it increasingly attractive to replace unpredictable operating expenses (wages) with predictable capital expenditures (robots).

The Honest Takeaway

As we close out 2025, my advice is to look where the crowd isn't. The “easy money” in LLMs has been made, but the “hard money” remains in robotics. The smart rotation for 2026 is toward the companies building the bodies and the simulation software that acts as their brain.

We should also watch the capital expenditure flows. AI data centers consume massive power and water, creating political and environmental friction. Robots consume batteries and sensors, scaling quietly inside warehouses and factories. As interest rates ease, the lower operating expense of a robot fleet becomes a compelling arbitrage for businesses facing labor shortages.

Happy New Year. See you in the future.

Sources:

Agility Robotics. (2024). Press Release: Opening of RoboFab Manufacturing Facility in Oregon.

Bloomberg. (2025). Artificial Intelligence Aggregate Index & Robotics Aggregate Index Data. Bloomberg Terminal.

Citrini Research. (2025). The Matrix Dojo: How Simulation is Solving Moravec's Paradox. Citrini Research Notes.

European Commission. (2024). The Impact of Demographic Change in a Changing Environment. European Commission Reports.

Huang, J. (2025, May). Interview on AI and Robotics Opportunity. Bloomberg Technology.

International Federation of Robotics. (2024). World Robotics 2024: Industrial Robots. IFR Statistical Department.

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (Japan). (2025). Population Projections for Japan: 2024-2070.

Statistics Korea. (2025). 2024 Birth Statistics. Government of South Korea.