The Great Labor Opt-Out

by Mardoqueo Arteaga

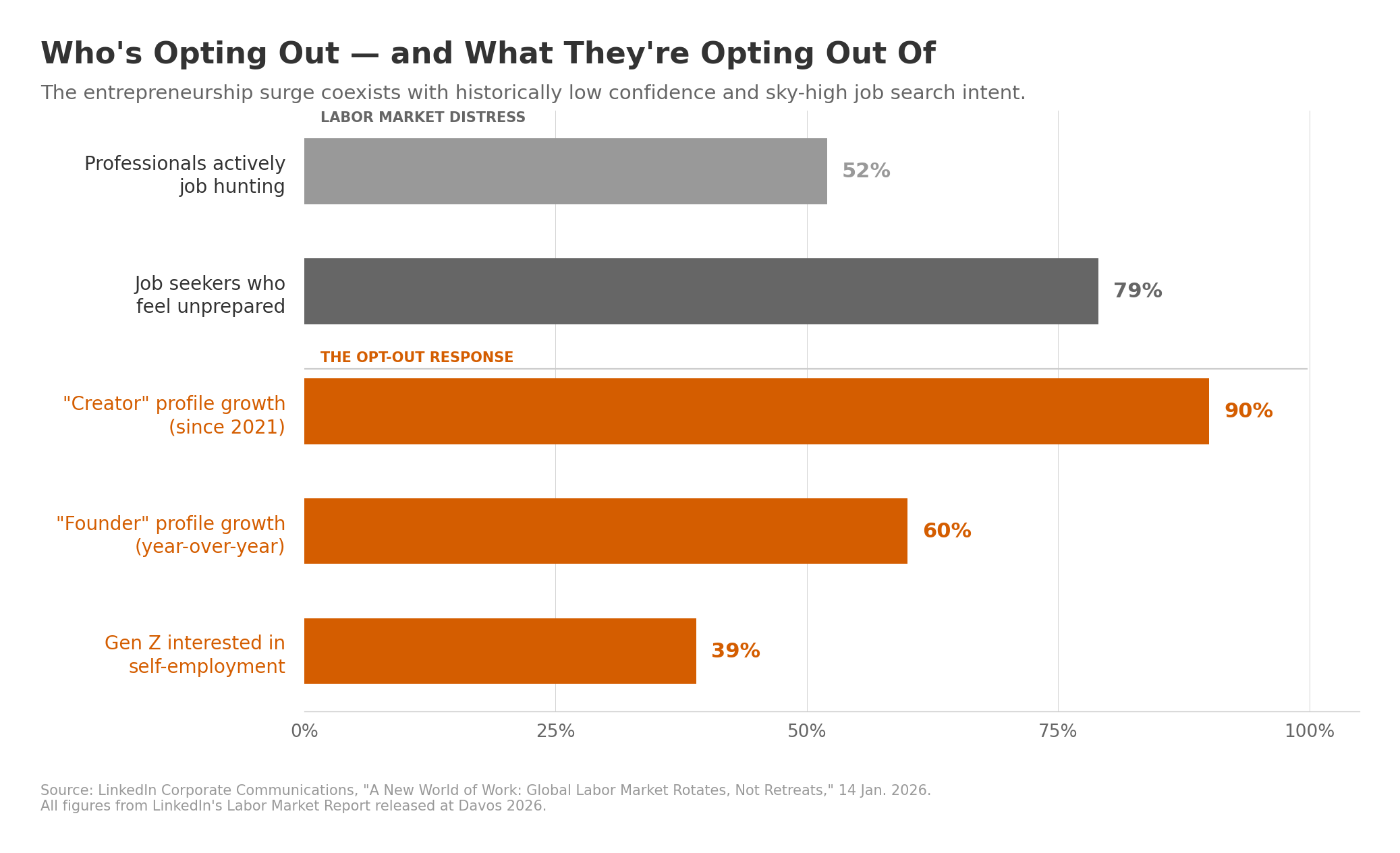

LinkedIn members adding ‘founder’ to their profiles grew 60% year-over-year globally. ‘Creator’ profiles surged nearly 90% between 2021 and mid-2025. Nearly 4 in 10 Gen Z professionals say they're interested in working for themselves.

The vibes-level interpretation is obvious: entrepreneurship is having a moment. AI tools are lowering the barrier to entry (we see videos on the platform about this all day), and the creator economy has gone mainstream. Side hustles are aspirational, and you could say that hustle culture won.

The economist's interpretation is a bit different and more uncomfortable in that this isn't a culture shift. It's a labor supply response to a broken outside option.

When the Outside Option Collapses

In the last edition of this blog, I wrote about a paradox in the labor market: 52% of professionals globally say they're actively job hunting in 2026, while nearly 80% feel unprepared to find one. Job transitions have hit a decade low while applications per opening have doubled since 2022. Hiring remains roughly 20% below pre-pandemic levels in advanced economies.

I called it a broken transmission mechanism, and that the feedback loop between applying for jobs and actually getting them has short-circuited. Here's what I didn't explore: what happens when that transmission mechanism stays broken long enough.

The answer, in any standard labor economics model, is that workers redirect their labor supply. When the wage-employment offer from employers deteriorates (aka when the probability of receiving a viable offer falls) workers who can exit the traditional labor market will. This is not necessarily because self-employment is better, but because the expected value of continued job searching has fallen below the expected value of going it alone.

This is textbook, but nobody is framing the entrepreneurship data this way.

The Census Data Tells the Same Story

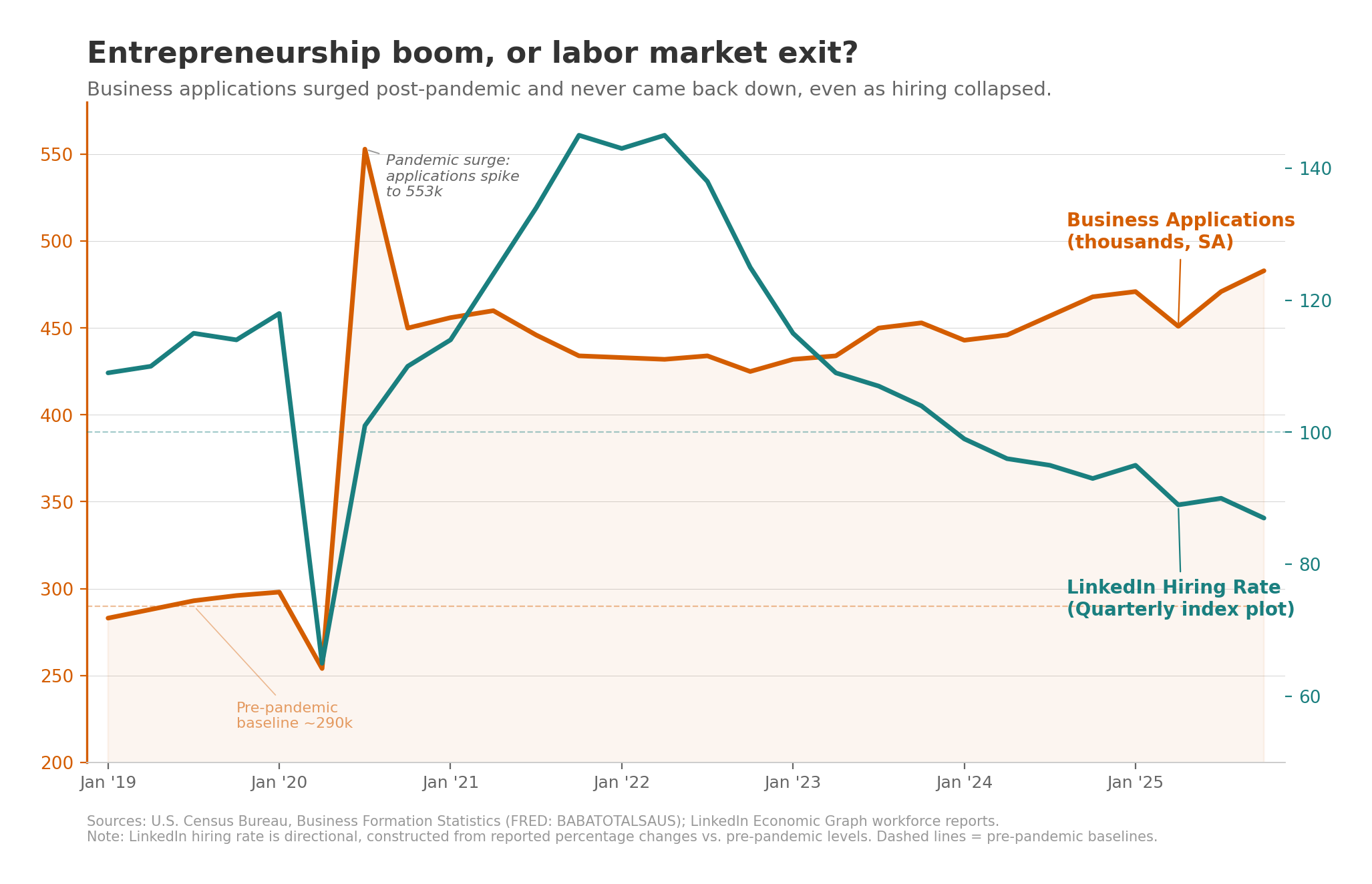

The surge in business formation isn't just a LinkedIn phenomenon. The U.S. Census Bureau's Business Formation Statistics, which track applications for Employer Identification Numbers, show that monthly business applications jumped from a pre-pandemic average of roughly 290,000 to over 400,000 in mid-2020, and they have never come back down. The most recent data, for December 2025, shows 497,046 seasonally adjusted applications. That's roughly 70% above the pre-pandemic baseline.

The initial interpretation of this surge, circa 2021, was optimistic. John Haltiwanger and co-authors at the Census Bureau documented what they called "surging business formation" during the pandemic, attributing it partly to pandemic-era reallocation: new businesses popping up in pandemic-friendly industries, workers discovering remote-enabled entrepreneurial opportunities, and a natural shakeup in the composition of economic activity. The post-pandemic startup boom was, in that reading, a sign of dynamism.

But dynamism has a shelf life as an explanation. The pandemic reallocation argument made sense in 2021 and 2022. It's harder to sustain in 2026, four years after the acute disruption ended. If this were simply creative destruction, you'd expect the application rate to normalize as the economy stabilized. It hasn't.

What has happened instead is that the labor market has settled into what Axios recently described as a "no-hire, no-fire" equilibrium: unemployment stays low at 4.4%, but hiring rates have been stuck at decade lows. Companies aren't laying people off, but they're not creating new positions either. Fortune 100 tech companies grew revenue 15% last year while growing headcount only 6%.

The Haltiwanger Inversion

Haltiwanger's work, particularly the 2014 Journal of Economic Perspectives paper with Decker, Jarmin, and Miranda, documented a decades-long decline in U.S. business dynamism. Startup rates fell from about 12% in the late 1980s to below 8% after the Great Recession. The share of employment accounted for by young firms dropped nearly 30% over 30 years. This was a structural story about rising barriers to entry, increasing market concentration, and declining labor market fluidity.

The post-pandemic surge in business applications appeared to reverse this trend. More people were starting businesses than at any point in the data's history.

But there's an important distinction Haltiwanger's framework helps us see. Not all business formation is the same. The Census Bureau distinguishes between total business applications and "high-propensity" applications, which are those most likely to result in businesses with actual payroll. High-propensity applications have also risen, but not as dramatically as total applications. A significant share of the surge is in lower-propensity applications: sole proprietorships, freelance entities, gig-economy registrations. In other words, people filing for an EIN because they need a legal vehicle to sell their labor independently.

This is what I'd call the Haltiwanger Inversion: the metric that once signaled dynamism (business formation) is now partly capturing its opposite. It's capturing workers who would prefer to be employed but who have been pushed out of (or frozen out of) the traditional labor market.

Who's Opting Out and Why It Matters

The generational data sharpens the picture. LinkedIn's report found that nearly 4 in 10 Gen Z professionals are interested in self-employment. You could read this as generational preference: Gen Z values flexibility, autonomy, purpose over pay. And some of that is true.

But Gen Z is also the cohort facing the most brutal entry-level labor market in years. Entry-level software engineering hiring is at decade lows. Computer science graduates hit record highs above 140,000 in 2024–2025, a 75% increase in supply since 2017. The traditional pathway of ‘graduate, apply, get hired, climb’ is clogged.

When the pipeline is clogged, workers route around it. The interest in self-employment among early-career professionals is just as much about values as it is about revealed constraints.

Meanwhile, the LinkedIn data on ‘creator’ profiles growing 90% since 2021 maps directly onto a labor market where the application-to-hire ratio has collapsed. Content creation offers what the job market no longer does: a feedback loop. You post, you see engagement (or you don't), you adjust. The signal is noisy, but it's a signal. Compare that to applying for 100 jobs and hearing nothing. In terms of information value, a TikTok view count is more informative than most job applications in 2026.

This is, from a behavioral economics perspective, the same mechanism I study in household expectations: people update their beliefs based on signals they can perceive. When the labor market stops sending signals, workers seek out environments that do even if the economic returns are worse.

The B2B Ripple Effect

This matters beyond the labor market. When workers exit the traditional employment pipeline and enter self-employment, it changes the composition of B2B demand. Sole proprietors and micro-businesses buy differently than employees at mid-size firms. They have different software needs, different purchasing cycles, different decision-making processes. They are more price-sensitive, more churn-prone, and less likely to sign multi-year contracts.

If a meaningful share of the business formation surge represents displaced labor rather than genuine entrepreneurship, then the B2B economy is experiencing a structural shift in its customer base, one that most companies probably haven't accounted for. LinkedIn's own Executive Confidence Index, falling across advanced economies throughout 2025, may partly reflect this: business leaders sense that something has changed in the demand landscape, even if they can't name it.

The Davos report also flagged that emerging markets like India (+40% hiring) and the UAE (+37%) continue to show momentum while advanced economies stagnate. This divergence is consistent with the outside-option story: in markets where traditional employment is expanding, you don't see the same push into self-employment as a fallback. The "opt-out" is concentrated where the employment channel has degraded most.

What Kind of Dynamism Is This?

I want to be careful not to overclaim. Some of the business formation surge is genuine entrepreneurship. AI tools have meaningfully lowered the cost of starting a business. Generative AI makes it possible for a single person to do the work that previously required a small team: design, copy, coding, customer support, making photos of an otter on a plane. The tools argument is real, and I don't dismiss it.

But the tools argument alone can't explain why business applications stay elevated while hiring stays depressed. If this were purely technology-enabled opportunity, you'd expect to see it alongside a healthy labor market, not in opposition to one. The fact that the two series are moving in opposite directions (applications up, hiring down) is the strongest evidence that the labor supply channel, not the technology channel, is doing most of the work.

Haltiwanger's earlier research showed that declining business dynamism was a drag on productivity because it reflected rising barriers to entry and declining reallocation. The current surge could be a drag for the opposite reason: not because there's too little entry, but because the entry is being driven by workers whose comparative advantage may lie in employment, not entrepreneurship. Necessity entrepreneurs tend to form lower-productivity firms. If a significant share of new business formation is necessity-driven, the aggregate productivity implications are ambiguous at best.

Sources:

Decker, Ryan A., John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda (2014). "The Role of Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism." Journal of Economic Perspectives 28, 3:3–24.

Decker, Ryan A., John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda (2020). "Changing Business Dynamism and Productivity: Shocks versus Responsiveness." American Economic Review 110, 12:3952–90.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "Business Applications: Total for All NAICS in the United States (BABATOTALSAUS)." FRED, fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BABATOTALSAUS.

Haltiwanger, John. "Surging Business Formation in the Pandemic: Causes and Consequences." Presented at Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2022, www.bostonfed.org/-/media/Documents/events/2022/labor-markets/papers/surging-business-formation-in-the-pandemic-causes-and-consequences-haltiwanger-decker.pdf.

LinkedIn Corporate Communications. "A New World of Work: Global Labor Market Rotates, Not Retreats." LinkedIn Pressroom, 14 Jan. 2026, news.linkedin.com/2026/2026-Davos-Press-Release.

Peck, Emily. "AI Helps Explain Why Companies Aren't Hiring — or Firing." Axios, 25 Jan. 2026, www.axios.com/2026/01/25/ai-jobs-market-hiring-firing.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "The Employment Situation — December 2025." Bureau of Labor Statistics, 10 Jan. 2026, www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

U.S. Census Bureau. "Business Formation Statistics, December 2025." U.S. Census Bureau, 14 Jan. 2026, www.census.gov/econ/bfs/pdf/bfs_current.pdf.

World Economic Forum. "AI Has Already Added 1.3 Million Jobs, LinkedIn Data Says." World Economic Forum, 14 Jan. 2026, www.weforum.org/stories/2026/01/ai-has-already-added-1-3-million-new-jobs-according-to-linkedin-data/.