The AI Paradox: Why Your New Colleague Is Only Coming for Your Entry-Level Job

by Mardoqueo Arteaga

Last week, I attended a gathering of economists and data scientists from major tech companies, all focused on how technology is reshaping business and work. Practitioners swapped insights on everything from labor market trends to AI experiments. The AI revolution promises to upend how we work and this is happening against the current backdrop of the “pause economy” with hiring and investment in a cautious lull. The discussions ranged from the cooling tech job market to cutting-edge methods in causal inference and AI measurement, and deeper questions about whether AI is a substitute for human work or a “bicycle for the mind.”

Below I distill three major takeaways from the event, along with why they matter for professionals navigating this new landscape.

Takeaway 1: The Tech Hiring Freeze and the Rise of the “Pause Economy”

In a previous post, I spoke before about the “pause economy”, and the theme persisted into this conference. Economists noted that tech job postings have plunged and stagnated after the pandemic boom; Indeed’s data shows U.S. tech job postings in mid-2025 were 36% below their pre-pandemic level. Unlike past downturns, this slump hasn’t quickly rebounded. Companies that hired feverishly in 2021 have pulled back just as hard, and ongoing geopolitical and economic uncertainties have businesses collectively hitting pause on new hiring. The result is an economy that hesitates where firms delay expansion and workers cling to current jobs, waiting for clarity.

Nowhere is this pause felt more acutely than for entry-level tech roles. Senior roles are far outpacing junior ones in new openings. In fact, entry-level tech job postings are down 34% since 2020, while senior-level postings fell only 19%. As one tech economist quipped, “hiring a more junior person is not as top of mind as it used to be” now that AI can handle some routine tasks. Instead, companies are looking for experienced talent who can leverage AI and data, effectively expecting one seasoned hire to do the work of many. There’s evidence of this bifurcation: machine-learning engineer postings have actually increased by 59% since 2020, even as general software jobs declined. In other words, demand is high for the specialized experts who can build or harness AI, but low for those expected to merely carry out routine coding or analysis.

Why this tilt toward seniority? One reason discussed is that generative AI and automation are starting to handle entry-level tasks (basic coding, drafting reports). This means new graduates face a tougher path with fewer openings and higher expectations when they do land a role. On the flip side, experienced economists and data scientists find their strategic and leadership skills more valued than ever. Several speakers emphasized a silver lining: human skills like problem-solving, team leadership, and communication have become more important. When routine tasks are automated, the hard problems that remain require creativity, judgment, and the ability to explain “why this is important” to decision-makers.

Taxonomy wise, many companies don’t even have an “economist” job title or family. Firms like Netflix and Amazon often slot PhD economists into Data Scientist or Analyst roles on product and revenue teams. One veteran advised younger economists not to fixate on job titles, but on the work content, such as influencing product strategy and bringing that counterfactual thinking economists excel at. There was broad agreement that you can have an “economist’s impact” without the label, and it’s often easier to get hired and benchmarked for pay in a data science track. In today’s pause economy, being flexible about how you apply your skillset (and focusing on business problems rather than academic puzzles) is key to building a career. As the legendary late Pat Bajari taught, much success can come from working backwards from business problems rather than forward from theory. Economists who can speak the language of product managers and executives (instead of p-values alone) are the ones driving value now.

What does this mean for the rest of us? If you’re an early-career professional in tech or data, temper your expectations in the short run: the competition is stiff and the hiring cycles are slow. Use this pause to invest in skills that algorithms can’t easily replicate: domain expertise, project management, storytelling with data, and yes, people skills. The jobs are still there (tech employment in computing roles is actually about 19% higher than in 2019 despite recent dips), but the bar to land one has risen. And if you’re running a business, recognize that we’re in a collective holding pattern. As one panelist put it, “we are choosing security over growth.” That won’t last forever, but while it does, doubling down on developing your existing talent, rather than aggressive expansion, is the rational move.

Takeaway 2: New Tools for Causal Inference and the Measurement of AI’s Impact

Economists in tech are rolling out ingenious new methods to answer hard questions. A highlight was MIT professor Alberto Abadie’s talk on Synthetic Control Methods. Essentially, this was on how to run an experiment when you can’t actually run an experiment. Many of the most important policy and business questions (did a city’s new minimum wage help or hurt?) can’t be studied with a classic randomized trial because you only have one Chicago or one Germany. Abadie’s solution: treat it like building a recipe. To estimate the effect on, say, Germany’s growth if reunification hadn’t happened, you construct a “synthetic Germany” from a weighted blend of other countries’ data. The technique mathematically finds a set of comparison units that mimic the treated unit’s pre-event characteristics, providing a plausible counterfactual. He extended this idea to what he calls synthetic control experimental design. For example, imagine a rideshare company wants to pilot a new pay incentive in a few cities. Pure randomization might assign Boston and Seattle to treatment, but if those cities are unusual, the experiment won’t generalize. Instead, one could intentionally select a treated city and a control city that together resemble the national market, using synthetic control logic to pick them. This minimizes bias when only a few units can be tested. The takeaway: even in the messy real world of business, we can design quasi-experiments to get closer to causal truth. As data scientists jokingly say, “If you can’t A/B test the whole world, you find a clever Plan B.” To be fair, they’re not known for their sense of humor.

This experimental mindset was everywhere at the conference. Airbnb’s economists spoke about geo-based holdout tests to measure advertising incrementality. Wayfair’s team described simultaneous experiments tweaking product prices and ad spend to find profit-maximizing combos. The common thread is that in tech, decision-makers crave rigorous measurement and economists are delivering by creatively adapting methods. It’s an arms race between complexity and our ability to decode it with data. As one speaker noted, the days of trusting a marketing campaign just felt effective are over; if you can’t quantify it, good luck getting budget.

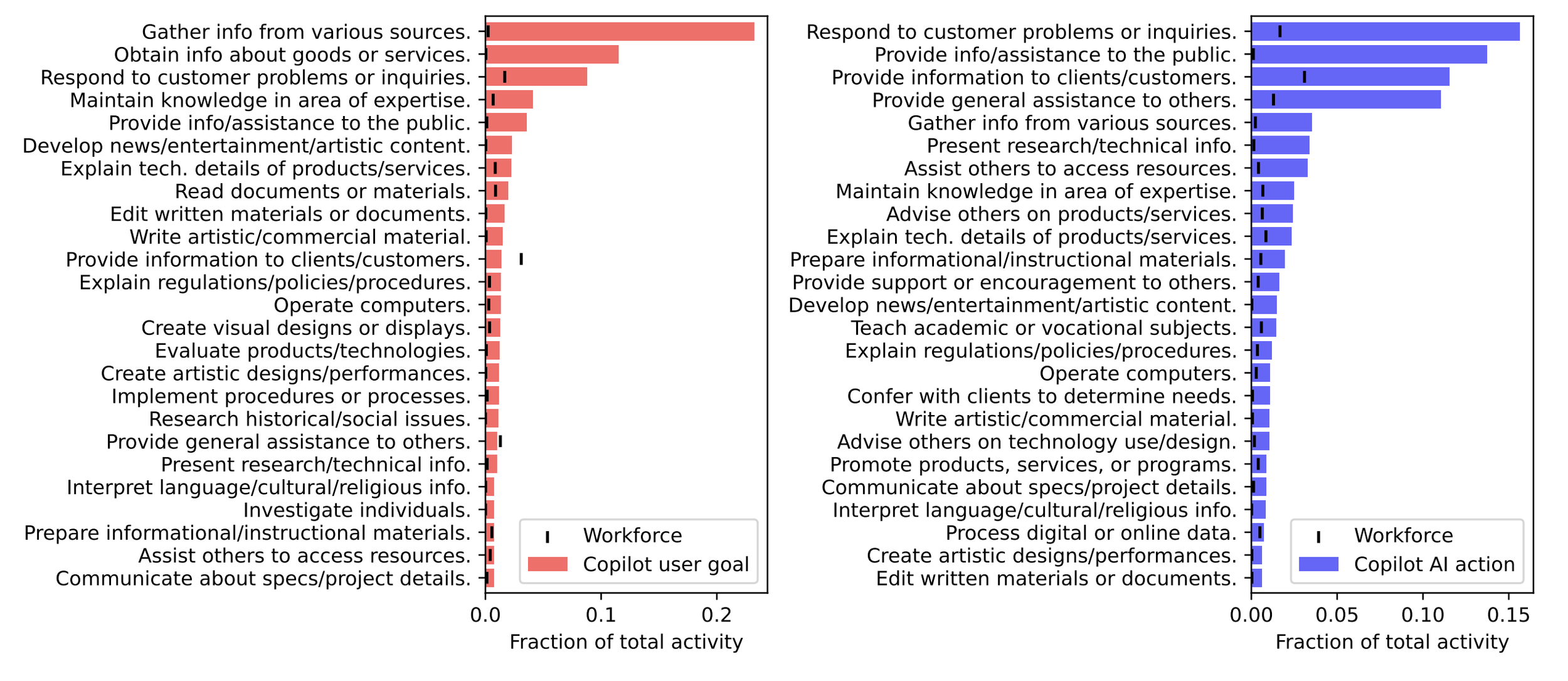

One of the most exciting areas of measurement is the impact of Generative AI on work. Rather than speculate, a team at Microsoft Research led by Sonia Jaffe is analyzing real usage data to see how AI is actually being used on the job. They combed through 200,000 anonymized conversations with Bing’s AI copilot to classify the tasks people sought help with. This let them score which occupations are seeing more of their duties assisted or performed by AI. The tasks most commonly handed to AI? Gathering information and writing. Essentially, research and first-draft composition are where current AI shines. People frequently use it to brainstorm, summarize, or generate text. Meanwhile, the AI itself is performing tasks like providing explanations, tutoring, and advising in these chats. Crucially, they found AI struggles with tasks requiring deeper judgment or complex data analysis (things like interpreting data or creating visual designs got relatively poor satisfaction ratings). In contrast, drafting an email or answering a factual question went well.

Source: Fig. 3. Division of labor in AI-enhanced work, showing the disaggregated activities of the human user (goal) versus the AI assistant (action). Source: Tomlinson et al.

Another insight: in 40% of conversations, the user’s goal and the AI’s action were in completely different domains. For example, the user might be trying to “write a marketing plan” (their goal), while the AI’s action is “teaching the user how to structure a plan.” Users seem to prefer AI as a coach or assistant rather than an autonomous decision-maker. When the AI tried to directly give advice or make decisions, users were less satisfied than when it helped the user do it themselves. This reinforces a view of generative AI as a tool for augmentation, not pure automation. It’s like having a very knowledgeable intern: great for research and grunt work, but you still want the human in the loop for the final call, especially if judgment is involved.

From this research, the occupations most applicable to AI assistance are not just the usual suspects of software coding, but also roles heavy in communication and paperwork. Think of sales, HR, or administrative support. These are jobs that involve a lot of emailing, scheduling, drafting documents. These have high “AI applicability scores” because a big chunk of their tasks involve information processing. By contrast, jobs with physical duties (a truck driver, a nurse) or purely interpersonal ones aren’t seeing AI step in much. No surprise, as today’s AI can’t drive a truck or genuinely empathize with a patient; stay tuned as that may change in the coming years. Interestingly, this measured pattern of impact lines up with some expert predictions. But the granular data also challenge broad-brush fears. No occupation in their analysis was anywhere close to fully automated by AI; rather, most jobs have a subset of tasks (often the tedious ones) being efficiently offloaded to chatbots. If you’re a professional, this means you should expect AI to take over slices of your work (say, drafting routine emails or summarizing reports), freeing you to focus on the higher-level or human-touch aspects.

Takeaway 3: AI as a “Bicycle for the Mind” - Augmentation Over Automation

A recurring debate was whether AI will ultimately replace human expertise or enhance it. One speaker invoked Steve Jobs’ famous metaphor of the computer as a “bicycle for the mind”, a tool that amplifies human capability. The consensus at this conference tilted toward AI being an amplifier, not a freelancer’s pink slip. Yes, AI can automate tasks, but it also makes human judgment more valuable. As evidence, early studies show AI assistance often benefits less-experienced workers the most, helping them close the performance gap. For example, in customer support, junior agents who used an AI tool saw their productivity jump to near the level of more senior reps. This hints at a short-run equalizing effect: AI can level up those with weaker skills. Indeed, a prominent finding presented was that initially AI may “temporarily reduce inequality by substituting primarily for implementation skills”, allowing a broader range of people to achieve competent results.

However, the long-run view is more sobering. As AI handles the easy stuff, the hard stuff ( requiring creativity, strategy, “opportunity judgment”) is what remains. The people who excel at those will become even more valuable. As AI advances, the relative value of human judgment is likely to rise. We could eventually see a U-shaped impact on inequality: a dip as AI lifts the bottom, then an increase as those at the top (who can harness AI to do truly innovative things) pull away. Put simply, your ability to ask the right questions, discern true signals from AI outputs, and contextualize them will be at a premium. AI isn’t coming for all our jobs, but it might sharply change what skills are rewarded. One tech leader noted that fully automating high-stakes decisions is often not feasible and that, rather, it’s the combination of AI speed with human oversight that delivers the best results. This complements the empirical finding that, for now, humans prefer to use AI as a tool rather than take its advice blindly.

The practical challenge many highlighted is the current productivity paradox of AI. Despite the hype, there are reports that deploying AI broadly has, in some cases, slowed things down in the short term. A 2024 Upwork survey found that while 96% of C-suite executives expect AI to boost productivity, 77% of employees say these tools have actually decreased their productivity or increased their workload so far. How can that be? Because introducing AI into workflows often means workers must learn new systems, double-check AI outputs, and handle greater complexity (think of a copywriter now also needing to be an AI prompt engineer and editor). More than half of workers in that survey said they received no training on these tools, and nearly half couldn’t see how to use them to meet their performance goals. In short, many organizations dropped AI into employees’ laps without changing anything else. This echoes the lesson from past tech revolutions: you can “see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics,” as economist Robert Solow famously quipped. It often takes years, and complementary changes in processes and skills, for a technology’s potential to translate into real gains.

The message for leaders and workers alike is to approach AI adoption as a socio-technical transformation, not a plug-and-play boost. Some companies are starting to get it right. One presentation discussed how Netflix balances LLM (large language model) evaluations with human feedback to judge content quality. They use AI to quickly flag, say, whether a TV show synopsis aligns with writing guidelines, but they still rely on actual user data (which synopsis led to more viewers clicking “play”?) to make final decisions. This “human in the loop” approach acknowledges that AI can drastically speed up certain evaluations, but human preferences and business context must remain central. Likewise, on the labor platform Upwork, researchers found that freelancers used new generative AI tools in different ways depending on their experience. Higher-earning freelancers leveraged AI to bid more confidently and take on fixed-price projects, essentially using it to increase the value and speed of their complex work. Lower-earning freelancers, in contrast, used AI to churn out more low-level tasks quickly, often bidding cheaper to win gigs. Both groups became more efficient, but their strategies diverged. The lesson is that AI shifts what people do and how they do it. Those who figure out how to complement their skills with AI (and not just use it for volume) tend to move up the value chain.

So, is AI coming for your job? The honest answer from these tech economists: it’s coming for parts of it, especially the parts that are routine, repetitive, or can be learned from patterns in vast data. But if you lean into the uniquely human aspects of your role, AI becomes a tool that makes you more effective. AI is your new colleague: incredibly fast, encyclopedic in knowledge, impressively literal, occasionally clueless. Train it well and watch it; neither fear it nor ignore it.

In this sense, adopting AI in your workflow is less like handing over the keys to a self-driving car and more like riding a bicycle: you still have to pedal, but you’ll go farther and faster than before.

Conclusion: Finding Opportunity Amid the Disruption

If you’ve made it this far and feel a bit overwhelmed by talk of hiring freezes, synthetic experiments, and AI paradoxes, let’s translate it into plain advice:

First, accept the pause without paralysis. The current hiring slowdown in tech is a regrouping phase, not a permanent decline. Use it wisely. For individuals, that means shoring up your fundamentals and acquiring the skills that are in demand (data analysis, yes, but also writing, leadership, domain know-how). Remember that even as entry jobs tighten, the overall tech workforce is larger than it was a few years ago. The doors have just gotten pickier (somewhat like getting into Berghain). For firms, the “frozen” labor market is an opportunity to train and reorganize your teams for when growth resumes. Investing in your existing talent’s AI capabilities and strategic thinking will pay off more than panic hiring or outsourcing in this climate.

Second, treat AI as an augmentation tool (your bicycle for the mind) and recalibrate expectations accordingly. Don’t assume throwing AI at a problem automatically yields efficiency. Just as businesses in the 1990s had to rethink processes to use computers, today we have to redesign workflows to integrate AI. If you’re a manager, pair lofty productivity goals with concrete training and a culture that encourages learning (and even failing) with new tools. If you’re an employee, don’t be discouraged if using AI feels awkward at first. Focus on specific tasks where it helps you save time or improve quality. Build your “prompt engineering” muscles, but also your editing and critical thinking skills to verify AI output. The organizations (and careers) that thrive will be those that master the mix of human and machine strengths.

Finally, double down on what makes you uniquely valuable. A point that came up again and again is that economists and analysts succeed in tech not by being translators and strategists. Your ability to frame the right question, design a clean test, interpret ambiguous data, or narrate a compelling story from numbers are hard to automate. One veteran explicitly said he hires people who can “explain to the C-suite why this finding is important.” In an age of infinite information, meaning is the scarce commodity. Whether you’re an economist, an engineer, or an entrepreneur, hone the skill of extracting meaning and direction from the noise. That might mean becoming the person in your team who best understands customer behavior, or who can connect technical results to business strategy, or who mentors others through change. These are the roles where demand will exceed supply.

I’ll close with this: embrace pragmatism over panic. Stay honest, stay curious, and rather than fearing the bicycle, start pedaling.

Works Cited:

Abadie, A., Diamond, A. and Hainmueller, J. (2015), Comparative Politics and the Synthetic Control Method. American Journal of Political Science, 59: 495-510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116

Abadie, Alberto, and Jinglong Zhao. "Synthetic Controls for Experimental Design." 2025. arXiv, arXiv:2108.02196.

Agrawal, Ajay K. and Gans, Joshua S. and Goldfarb, Avi, The Economics of Bicycles for the Mind (July 07, 2025). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5347891

"Berghain." Wikipedia, [5 Nov. 2025]. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berghain. Accessed 17 Nov. 2025.

Bernard, Brendon. "The US Tech Hiring Freeze Continues." 30 July 2025. Indeed Hiring Lab, https://www.hiringlab.org/2025/07/30/the-us-tech-hiring-freeze-continues/.

Hardesty, Larry. "TEC: A Young Conference for an Emerging Field." 9 Nov. 2020. Amazon Science Blog, https://www.amazon.science/blog/tec-a-young-conference-for-an-emerging-field.

"Productivity Paradox." Wikipedia, [10 Nov. 2025]. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Productivity_paradox. Accessed 17 Nov. 2025.

Tomlinson, Kiran, et al. "Working with AI: Measuring the Applicability of Generative AI to Occupations." 2025. arXiv, arXiv:2507.07935.

The Upwork Research Institute. "From Burnout to Balance: AI-Enhanced Work Models." 23 July 2024. Upwork, https://www.upwork.com/research/ai-enhanced-work-models.